The role of ideologues

This is the fourth Q&A of the interview series with Ahmed Al Hamdan (@a7taker), a Jihadi-Salafi analyst and author of “Methodological Difference Between ISIS and Al Qaida“. Al Hamdan was a former friend of Turki bin Ali, and a student of Shaykh Abu Muhammad Al Maqdisi under whom he studied and was given Ijazah, becoming one of his official students. Also, Shaykh Abu Qatada al Filistini wrote an introduction for his book when it was published in the Arabic language. The interview series contains contains five themes in total and will all be published on Jihadica.com. You can find the first Q&A here, the second here and the third here.

Tore Hamming:

Part of the struggle between IS and AQ happens through ideologues either part of or sympathetic to one of the two movements. AQ has consistently been supported by major ideologues like Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, Abu Qatada al-Filastini and Hani Siba’i, while IS has relied on younger people, most famously Turki al-Bin’ali. How do you see the role of these ideologues for the broader struggle within Salafi-Jihadism?

Ahmed Al Hamdan:

In fact, this question has been phrased wrongly.

We must realize that the problems of ISIS are no longer confined to a conflict with Al Qaeda in just the Arab region only making the Arabs to be the only influential speakers for Jihad. Rather ISIS has come to every language and nationalities! And they have come into conflict with groups that are not Arabs. These nationalities and groups have speakers that speak in their languages and influence them more than the Arab speakers. I will give you an example:

Amongst the English speakers, Shaykh Anwar al Awlaki is considered to be one of the main leaders and ideologues of Jihad, while amongst the Arabic speakers he is considered to be a Jihadi commander only. Why? It is because all the Shariah treatises of Shaykh Anwar have been released in the English language. They were not released in the Arabic language with the exception of 4 statements, which were all exhortative statements.

So if we compare for example the influence of Shaykh Anwar al Awlaki amongst the English speakers with that of the influence of the Shaykhs such as Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi and Abu Qatada al Filastini, there is no doubt that Shaykh Anwar al Awlaki would be much more influential. And this can also be seen with the American Shaykh Ahmad Jibril. I myself and some of those occupied with the Arab Jihadi issues had never heard of him at all until recently when communicating with the English Jihadi media. And we came to know that this person has a lot of influence and is widely known, despite us having not heard about him at all before.

And this is a general principle: The more material exists for a person in a specific language, the more will be his influence upon the speakers of that language. How many materials of the ideologues of Jihadi groups in Arabic have been translated into Turkistani language for example? Maybe 2 or 3. So is this sufficient to influence the Turkistanis in the battle against ISIS? The answer is no. However when a person like Mufti Abu Dhar Azzam break away and release a statement criticizing ISIS, this will have a greater effect than translating some articles of al Maqdisi and al Filistini about ISIS into the Turkestan language, even if he is less knowledgeable than them. Why is this so? Because Abu Dhar is known amongst the Turkistanis and he speaks in their language and he has held lectures and lessons among them. And so, being previously known as well as a common language is what becomes effective for having influence in battles, and not just Shariah knowledge.

Who is the foremost ideologue for Jihad and the Jihadi groups in Europe? We don’t know. Perhaps a Shaykh who is young in age and who speaks French will have a greater influence than Shaykh Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi or Abu Qatada al Filistini upon the Jihadis who speak in French.

So the person who speaks directly to you and who always keeps you at the center of the events will be more effective than a person with Islamic knowledge who does not speak directly to you and who has to use interpreters who may be late in translating his statements or may not translate all of his statements.

However because of the worldwide battle against ISIS, there have emerged communication bridges between groups who are fighting against ISIS who speak different languages. For example, we see that Dr. Ayman al Zawahiri’s words get translated into Russian by the Islamic Emirate of the Caucasus (1) or get translated into Turkistani by the Turkistan Islamic Party, (2) and we have seen Shaykh Ayman trying to address these organisations by mentioning their merits. And we have seen how the ideologues and the leaders of the Arab groups have released statements in solidarity with the Islamic Emirate of Caucasus against the attempts of ISIS to split its ranks, (3) and we have seen how when the Turkistan Islamic Party released a speech from its top most leader refuting ISIS, they put the Arab scholars of Jihad in the background. (4)

So I think we are facing a situation known as “the globalization of the Jihadi organisations” in contrast to “the globalization of ISIS.”

And this has resulted in intermingling and openness towards each other due to the existence of a common enemy. Previously the Russians were fighting the Caucasians and the Chinese were fighting the Turkistanis and the Americans were fighting Al Qaeda, most of whom have been Arabs. However these organisations have now found themselves against a united common enemy, which is ISIS, which is trying to dismantle them. And this has led to them eventually coordinating with each other to fight this new enemy which is threatening the fortresses from within, as opposed to the enemy which is not common to them all and threatens the fortresses from the outside.

And this is another principle: Whenever there is a single enemy, there is a larger chance of unity and cooperation.

So due to this, there began to circulate writings which refute ISIS and translated works have begun to spread in different languages about a single issue only, that is refuting the misconceptions caused by ISIS. And I think this is something that has not happened before.

This is one matter. As for the other matter, it is why have younger ideologues inclined towards ISIS, while their teachers have inclined towards Al Qaeda?

I have answered this question in my previous reply, and I have said that the greater a person’s age and the more his experience in life, the greater will be his caution in dealing with any newly occurring matter, as opposed to the one who has no experience and whom you mostly see acting without forethought and who is more emotional rather than being logical.

Secondly, these students took the lead at a time when those Shaykhs were imprisoned- I mean the two Shaykhs Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi and Abu Qatada al Filistini. And I think they said to themselves that “we must fill the vacuum left by our Shaykhs”, and they put themselves on the same level of their Shaykhs, and they began to speak on fresh matters which are very complicated, in a manner which is different from that of their Shaykhs who used to be calm and careful. And here let me write a historical testimony:

Turki Bin’ali had gone to Syria twice. The first time, he claimed, he wanted to send relief aid, and the second time was the one in which he did not return. And before he went for his first time, he was told not to listen to only one side, specifically in the matter of the dispute between Jabhat un-Nusrah and ISIS. But when he returned from Syria, we sat down together, and there was a change in his tone of speech about Jabahat al Nusra and it had become very harsh. (5) And when he was asked and told “Have you tried to hear from Jabhat un-Nusra when you were in Syria to understand their point of view?” he said “No, rather the Islamic State and its representatives are trustworthy and they do not lie!”… And so there is no need to hear both sides…!

This is not something which someone else has told me, rather I saw it with my own eyes and heard it with my own ears. So all his books and speeches and articles with which he supported ISIS were built upon this foundation, which is hearing only from one side which as per his claim, does not lie. Then it became clear to us with the passage of time that these representatives would lie even in their official publications. So look at what happens when a student takes the place of a teacher while he is not qualified!!

On the other hand, Shaykh Abu Qatada was asked after 20 years, did he benefit from the events in Algeria when he was young. And he said “Yes, I have benefitted greatly, one of the most important of which was to not be deceived by the way how a questioner formulates his question, because sometimes he will lie and deceive and formulate questions which are not in accordance with reality in order to get the Fatwa he wants to support his stance against his opponents. So whenever I feel that a person is doing this, I would ignore his questions so that he does not take my Fatwas to misuse them in an improper manner”. (6)

But the person with little experience will fall into this mistake and he will sympathise with the questioner who has formulated his question showing him being oppressed, and he will issue a Fatwa according to what he likes and desires.

What makes a person forget himself or forget his real position is those around him, especially when they praise and exaggerate in praising the student of knowledge, and when he is addressed as ‘Shaykh’ and ‘scholar’ and with other such names. And when many people repeat these words it causes him to actually think that he has become a Shaykh and a scholar and that he is entitled to speak on the most complex matters. Therefore he should not be misled by such words of praise, and they must not cause him to forget his actual position. And if he knew what his actual position is, he will not be affected by such praises and speak on critical issues while not being qualified for it, because he knows his true worth, and he will not be carried away by these people who praise him as he knows that they are exaggerating or maybe they are exaggerating for other purposes, such as to cause you to fall into this trap, and hence you would be careful. But the one with little experience is often naïve and not cautious or aware.

In the end, how is it possible for the gap between the generations to have an effect in supporting different organisations? There is no doubt that the influence of the teachers is much greater, and the level of their fame and their positions are greater than these students who emerged only through the internet. Shaykh al Maqdisi is a person who is well-known to the most prominent leaders and to all the chiefs of the Jihadi movement, and likewise Shaykh Abu Qatada. They are considered by many as sources of reference on religious matters for Al Qaeda, (7) as opposed to these students who are not famous, because many of the students used to write under pseudonyms and some of them did not reveal who they are even to this day. So some are hesitant in promoting or mentioning people who are unknown, and many of them have stopped writing after joining ISIS.

And this is because of two issues. First, they are busy in teaching and education because ISIS have seized large areas in Iraq and Syria and it needs to fill this vacuum by teachers of Sharia, who hold seminars, speeches and lessons. And the one who becomes busy with that will find it difficult to write replies and research on the internet. The second issue is that which Shaykh Al Maqdisi himself informed me, from his contact with people in ISIS which was that the minister of information who was recently killed had prevented these people from writing under their real names, fearing that they would achieve high status and then split later, which could be used as propaganda to dissuade people from joining ISIS. Apart from that there is no doubt that the teachers are the ones with more influence and credibility than the students and they are ahead of them for the following reasons:

- Because their knowledge on religion and awareness on Islamic and religious matters is more than the students.

- Because they are well known and are people who had their stances and sacrifices and firmness that are known for over three decades, unlike many of the students who write under pseudonyms and who only jumped towards the forefront in few years and who are actually unknown, except to a small group of people, and their stances, sacrifices and firmness are unknown. And because of previous security issues there was a fear of promoting people who are unknown. (8) Thus many of these people have been ignored. As for those from the students who are known, they are not widely known amongst the Mujahideen and their sacrifices are nothing in front of those of their teachers who suffered trials and tribulations.

- Another issue is that the style of the Shaykhs when they respond would remain within the confines of scientific method, as opposed to the response of their students to their teachers. They would respond to their teachers by transgressing the boundaries of scientific method and go in a method which contains insults, rudeness and by using words of filth, derision and mockery, which would make them in a weaker position in the sight of the neutral observer.

ISIS knows that the teachers have a greater influence than their students. Because of that, even if some of the students join them, they would still not be content with that, rather they would be determined to discredit the Shaykhs by tarnishing their image. For example, the publication which was released under the title “Smashing the idol of Al Maqdisi” after Shaykh al Maqdisi became a mediator between them and the Jordanian government in the matter of the Jordanian pilot, Muadh al Kasasbah, they deliberately tried to confuse between “mediation” and “representation”, and they portrayed him as a representative of the government which he makes Takfeer upon. And hence because he has become their ‘representative’ then he has deviated from his path in the matter of disassociating from these governments. This is despite the fact that in the same recording, there are words which confirm that he is not a representative, such as him describing the Jordanian pilot as an apostate..!!

Another matter is that they have gone beyond the stage of confusing and gone into the stage of lying. They stated in one of their magazines, that Shaykh Abu Qatada has alliance to the Tawaghit! (9) This is despite the fact that just one week before the release of the magazine, Shaykh Abu Qatada wrote in a tweet “The Muslims have not stopped falling into the same mistakes which they made before, the crime of allying with the Tawaghit”…!! (10)

But why does ISIS strive so hard to do this? It is because they know that the students are not enough and that it is the teachers who have a greater influence.

ISIS is trying to neutralize the influence of these Shaykhs, and when they will no longer have influence, then their students will at once take a superior position. Shaykh Abu Ahmad al Jazaairi, who is a Shariah leader of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghrib, has spoken the truth when he said: “Bringing down the symbolic personalities means necessarily the rising of the inferior ones. The Prophet, peace be upon him, said “When there doesn’t remain any scholar then the people will take the ignorant ones as their leaders and they will be asked, and they will give Fatwas without knowledge, thus becoming misguided and misguiding the others”. (11)

==========================

Footnotes:

(1) It is the speech entitled “The scholar in action” which is part of the series “Carry the weapon of the martyr”. It has been translated by the media committee of the State of Dagestan VD.

(2) It is the speech “Turkistan- Patience and then victory” from the series (The Islamic Spring). It has been translated by “Sawt ul Islam” which is the media wing of the Turkistan Islamic Party.

(3) The joint statement “A statement about the recent events in the Causasus” issued on 28 January 2015, which had the participation of a group of Shaykhs the most notable being Shaykh Ibrahim Rubaish, Shaykh Harith al Nadhari, Shaykh Khalid Batarfi, Dr. Sami al Uraidi , Abu Maria al Qahtani and Dr. Abdullah al Muhaysini.

(4) A special interview by Sawt ul-Islam with the leader of the Turkistan Party, Shaykh Abdul Haq, in Feburary 2016

(5) As a fact, the tone of Turki Bin’ali regarding al Nusra was different in the past. I had written a response to one of the opponents, but before publishing it, I sent it to Turki Bin’ali in his Facebook account, on 20 October 2013. So he replied to me privately and said “May Allah bless you. These are beautiful points, but do not cause differences between JN and ISIS, for we are with JN against the Tawaghit and their lackeys, but we condemn their mistake in leaving ISIS”. But when he returned back from Syria, his stance became different and he no longer even agreed to spread the videos showing the operations carried out by Al Nusrah against the Tawaghit and their stooges. And he would compel you to take your stance and choose to support ISIS and be hostile to everyone who oppose them, the first and foremost being Jabhat al Nusra.

(6) Shaykh Abu Qatada said in his third audio meeting in Al Fajr room on Paltalk on 22 April 2015: “We benefited a lot from the experience in Algeria, and the greatest of them was in the problem of lying and using different technical words. For example, if a Sunni man from one of the Jihadi groups in one of the countries send you a message saying “Oh Shaykh, an innovator has appeared amongst us and we have found with him documents indicating that he will contact the regime to reconcile with them, and we have found with him documents showing that he is planning a coup to overthrow the leadership in order to reconcile with the regime and deviate the Jihad into such and such path etc.”, and you think that he is a Sunni. So what answer will you give him if you are a student of knowledge? The answer would be: He is causing corruption in the land, and the least you can do is stop him, and if you cannot end his innovation without killing him, then kill him. This is what the scholars say. But we would discover later on that the innovation was not like how the questioner had mentioned but it was something else. So is the mistake in your Fatwa, or is the mistake and the lie from the questioner? And because of that, the questions asked by some brothers would remain with me pending for months and I would not reply to them. They are trustworthy brothers but they narrate the incidents as they like and as they see.

(7) Shaykh Ayman Al Zawahiri in his book “The Exoneration” has considered Shaykh Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi as a reference point for Al Qaeda (p.44) as well as Shaykh Abu Qatada (p.47). And Turki bin Ali wrote a book entitled “Al Qawl An-Narjisi Bi Adaalat Sheikhina Al Maqdisi” (a book containing collections of statements from different scholars who spoke about the virtue of Sheikh Maqdisi and praised him) and another book “Al Qilaada Fee Tazkiyath Sheikhina Abu Qatada” and in these two books Bin’ali gathered a collection of testimonies of Jihadi leaders from all the fronts of Jihad regarding these two Shaykhs. The students of these Shaykhs did not gain even a small fraction of the trust that the leaders of Mujahideen have in these Shaykhs.

(8) Leadership status in the Jihadi organisations should only be given to a person who has undergone hardships and trials and has remained firm. Shaykh Usama Bin Ladin says while putting down the condition to qualify for leadership that “It is necessary that the top level leadership be from those who have been tested and examined thoroughly.” [First set of Abbottabad Documents, Index number- SOCOM-2012-0000016] And one of the types of this test is to go to battles and fight, because the spy often sells his principles in exchange for money in order to live, but in the battles there is a very big possibility for him to get killed and so his true nature will be seen. Shaykh Usama bin Ladin says: “For example, here we feel reassured when people go to the front lines and get tested there” [First set of Abbottabad Documents, Index number: SOCOM-2012-0000003]. And from previous experience, the Jihadi groups learnt about the problem of the leadership being taken over by people who are unknown or who did not have any previous experience in the field of trials. Muhammad Suroor Zayn al Abideen (the one to whom the Suroori movement has been ascribed to, which is a Salafi school of thought) who had associated with some people who were involved in the Syrian Jihadi during the Eighties, had mentioned the incident of the infiltration into the leadership by a person named as Abu Abdullah al Jasari who used to read the Quran a lot and offer prayers at night and wake the youth for prayer, and just because of these actions he was made part of the leadership even though he was unknown and no one from the Islamic groups knew him. Then he took part in the arrest of Adnan Al Uqla and the top leadership and in aborting the armed struggle. (Refer to his book: How to protect the Islamic ranks from the hypocrites, p.77) Shaykh Abu Mus’ab al Suri has confirmed this information in his book “The Jihadi Islamic revolution in Syria – Experiences and Lessons” (p.150)

(9) The “Rumiyah” magazine, first issue, page 29-30, September 2016

(10) His personal twitter account is “@sheikhabuqatadh” on 25 August 2016. Link here

(11) His personal twitter account is “@ahmed_karim25” on 15 May 2016. Link here

Tore Hamming:

In terms of ideologues, the struggle between al-Qaida and the Islamic State could be framed as a struggle between teachers and their students. Have the teachers been rendered irrelevant by the fierce rhetoric or do they continue to influence Jihadi followers in great numbers? Or are new elements, like language, implying that new ideologues are shining in the increasing globalised Jihadi environment?

It is actually all about the language. Or almost. That could easily be the initial conclusion of Al Hamdan in his assessment of the influence of contemporary Jihadi-Salafi ideologues. The prominence of an ideologue is not necessarily dependent on his knowledge, or cultural capital, but to a great extent on his way of connecting with listeners. It is interesting to hear from a keen Jihadi follower like Al Hamdan that Ahmad Jibril was unknown to him until recently although he is a household name in many Jihadi circles in the West.

The above statement about the importance of language is only true to some extent. Despite the fact that most of their statement are in Arabic, the Jordanian ‘teachers’ of Abu Qatada and al-Maqdisi, who have been extensively studied in several articles on Jihadica, continue to be dominant voices among individuals sympathetic to the Jihadi project all over the world.

In a discussion I had with the London-based Abu Mahmoud al-Filistini about the importance of ideologues in the fitna between al-Qaida and the Islamic State, he told me that ideologues are by far the most actors in influencing people. “Even more than any military commander”, Abu Mahmoud said. This is also why it is so interesting to follow how these ideologues intervene in the fitna, who they side with and how they manage to influence ‘the masses’. As a result, it is not surprising that Jihadi groups and media organisations put a lot of effort into translating speeches, statements, videos etc. Almost every time I check my Telegram, there is an update on a new language added to the repertoire of a channel.

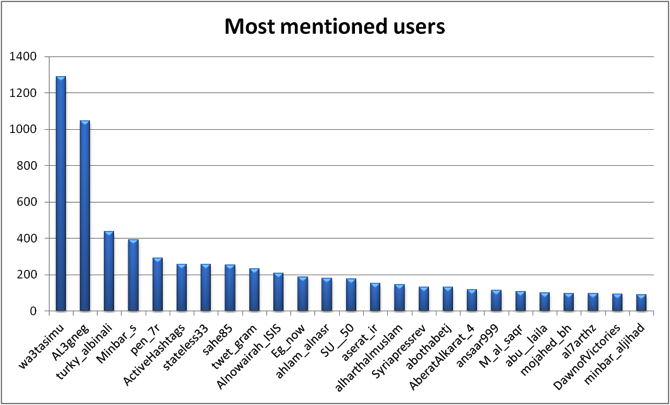

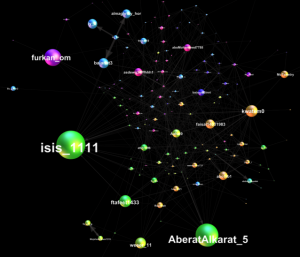

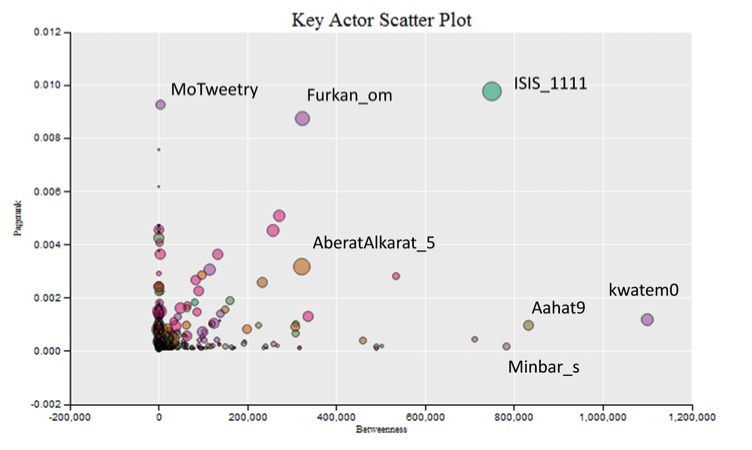

The competitive nature of the al-Qaida – Islamic State relationship is affecting the logic of the entire Jihadi field. Lately, this has been very evident in the case of Jund al-Aqsa. This competitive environment and the flexible position of many groups is not only considered a risk from an al-Qaida or an Islamic State perspective, but also as a potential. This is a central issue for Jihadi ideologues and the media supporting them as they seek to warn people against the opposing group, while promoting their own camp. In the case of Maqdisi, Abu Qatada, and Hani Siba’i they all have +50,000 followers on Twitter and their statements are discussed intensively and listened to. This mobilising power continues to be important for al-Qaida and is something the Islamic State is envying.

Initially, the students proved capable substitutes of the teachers, but as time is passing it is my impression that the latter is slowly regaining their importance in the eyes of Jihadis around the world.