Turning the Volume Up to 11 is not Enough (part 2): Networks of Influence and Ideological Coherence

On February 3, 2014, the self-proclaimed “Islamic State” (ISIS or ISIL) published a video depicting captured Jordanian pilot Mu’adh al-Kasasiba wearing the notorious orange jump suit. For the background information on the secret negotiation attempt for his release, please check out the detailed contribution by Joas. For this Jihadica posting, let us concentrate on the propaganda side – and works – of ISIS, as announced in our first part.

This post looks at three aspects;

• How this video fits into the greater puzzle of jihadist ideology including the intersection between text based ideology and the demonstration (via video) of this ideology in practice.

• How the elements of the Swarmcast ensured the video would reach a wide audience and maintain a persistent presence.

• The limited impact of the response, named #opISIS, by hackers linked to Anonymous seeking to disrupt ISIS media networks.

Content matters, as does the means of delivery of jihadist propaganda data and material. Both elements highlight coherence: ideologically as well as technically. The ideological coherence, the persistence of its narratives and pseudo-theological fundament that is translated so well by jihadist media activists into audio-/ visual works shows parts of the resilience and the media strategy, the incorporation of the ‘jihadist tradition’. The video seeks to attract Arabic-speaking and non-Arab audiences, published in Arabic with encoded subtitles in English, French and Russian. ISIS exercises technical coherence and resilience in terms of disseminating the video and its propaganda in general – which, by the way is neither special nor outstanding or genius but simple use of a range of platforms (social media, forums, YouTube) by highly dedicated individuals, which we term as media mujahiddin.

The video is entitled Shifa’ al-sudur, a reference to Qur’an (9:14), and used by ISIS to justify and project the message that they are acting on behalf of God to “heal the believers’ feelings” as al-Furqan translates the title. The reference shifa’ al-sudur is part of the jihadist propaganda ambition to appease their target audience with audio-visual content that showcases, among many elements, “revenge” or at least “retribution” for the civilian suffering inside Islamic territories – reserved for the Sunni population only within this notion and mindset of course. The successful media strategy employed by ISIS focuses on audio/-visual output claiming practical application and translation of ideology into action. This is juxtaposed with assumed seniority of al-Qa’ida, who are crafting jihadist dogma but have little to no space (or territory) for implementation.

ISIS understands the importance of making use of the territory they control and deploys media units in every “province” (walaya). As a result, they publish up to 4-6 videos a day showing; the “life in the caliphate”, executions, sentences of physical punishment (hudud) framed as an evident legal system, religious policing of communities, the destruction of shrines of saints as well as a romantic view on fighting, sacrificing and being passionate for the local Sunni population of the “caliphate.” In general, Jihadists seek to deceive and coerce by trying to conceal their human fallibility while portraying themselves as God’s spokespeople. Therefore, every piece of their oftentimes highly professional and sometimes sophisticated propaganda is part of a greater puzzle.

In this greater puzzle everything is sanctioned, scripted, subjected to ideology, and is an integral part of the Sunni ‘jihadist tradition’ dominated by Arab ideologues and primary Arabic language publications (textual and audio/ -visual). Ideology in theory and practice serves as the motivation and guidance, it is built on the fundamentals of theology and pieces of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), used and interpreted to serve the extremist cause. The citation of historical scholars such as Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), as well as quoting selected parts of Qur’an and Sunna out of context, are powerful tools for extremist ideologues and media workers. It provides leverage for a distinct identity established on the premises of being ‘true Muslims’ offering the ‘true Islam’ and openly challenging and discrediting the “palace scholars” (‘ulama’ al-salatin) worldwide.

The ‘state-owned ‘ulama’’ are defined as corrupt scholars who neglect the true nature of Islam and thus have become followers of the “program of falsehood (batil)” whereas the jihadi as the only true, steadfast servant of God portrays himself as the follower of the “program of truth (al-haqq). This is one of the fundaments of Sunni jihadist perception of community that has now led to the creation of an “Islamic State” where the “true” and “proper” principles and methodology of Islam can be realized.

Visual Culture

Videos are the most important mouthpiece to show the manifestation and realization of jihadist creed (‘aqida) and methodology (manhaj) for which they claim to live and die. The video discourse allows a constantly repetition and showcasing of doctrines that disparage non-believers and sanction the collective punishment of “apostates” (murtadd) and Muslim “hypocrites” (munafiq).

This theological led discourse can be defined as “discursive guidance.” By the constant repetition of extremist laden theological interpretation (texts) and its practical implementation (videos), jihadi media consumers and participants are guided into a specific notion that serves as the fundament to become active and potentially commit attacks.

The first posting regarding this video provides an overview of the video distribution via Twitter and the attempts at counter messaging. It shows that it is not enough to merely increase the volume of counter messaging, or even to be retweeted frequently; (counter) messaging must be able to penetrate the Jihadist clusters, especially across the range of languages, hence targeting the targeted audiences. If counter-messaging remains isolated, the result is less a counter message and more a separate conversation.

Shouldn’t “counter-messaging” or a “counter-narrative” rather seek to penetrate and at best infiltrate jihadist media clusters online in hopes of persuading consumers to turn away? On different levels?

In a future posting the specific messages that are encoded into this video will be detailed, for now let us assess some aspects of the Swarmcast phenomena through which the video was distributed; specifically, speed and resilience. The final section looks at the response from hackers who launched another wave of attacks on accounts they believed to be sympathetic to ISIS, or jihadist groups more broadly.

Swarmcast:

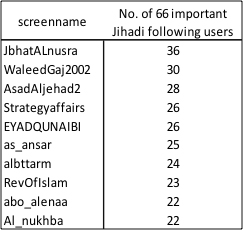

This section assesses some aspects of the Swarmcast through which the video was distributed; specifically, speed and resilience. Although some commentators and policy makers are tempted by the idea that suspending a few most active accounts could limit jihadist activity by reducing the number of users following selected accounts (discussed further here), data analysis of content distribution highlights that the Swarmcast can withstand such an approach.

Speed:

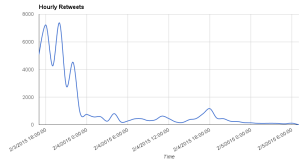

In the first six hours there were over 32,000 retweets containing the tag: #شفاء_الصدور . This is a combination of those actively disseminating the video and those engaged in counter-messaging. The volume of retweets and the speed with which that occurs renders the removal of accounts largely ineffective in disrupting the dissemination of content. By the time accounts are identified and suspended the content has been widely distributed.

Equally, the focus on retweets allows the analysis to focuses on a behavioral response – showing who Twitter users responded to – rather than those who are most active. Analysis of accounts that other users think are important is often more effective than examining the most active accounts – as these may have a lot to say, but that doesn’t mean anyone is listening.

Engagement Profiles:

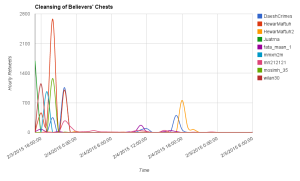

The Engagement profile of frequently retweeted accounts shows the same pattern of rapid information dissemination, with most activity occurring in the first six to eight hours. The intensity of engagement with accounts attempting counter-messaging is broadly speaking at the same time. This is a significantly faster response than that during the release of “the Clanging of Swords, part 4” (48 hours on that occasion). This speed of response may be because of the video having been published on a weekday, rather than a Saturday.

click to enlarge (interactive)

click to enlarge (interactive)

The data shows that trying to remove individual videos or user accounts one-by-one, leads to a global game of whack-a-mole, a strategy ISIS seems to be employing on the battlefield as well.

This absorbs resources, while the media mujahedeen move fast enough to maintain a persistent online presence.

Resilience:

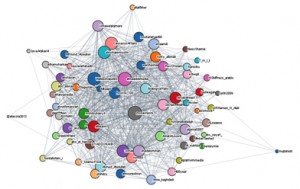

As discussed in previous pieces, degree of interconnection between accounts gives the cluster of users disseminating Jihadist content a level of resilience which, in addition to speed discussed above, enables the network to maintain a persistent presence. This highlights the importance of challenging the networks that distribute content rather than chasing after lists of individual accounts.

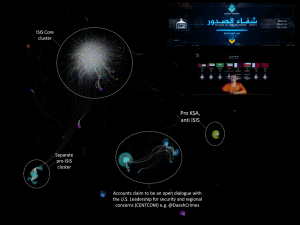

As discussed in the earlier post the network image visually attests that there are different clusters of users sharing content and that users sharing counter-messaging were almost entirely isolated from core media mujahedeen accounts.

Focusing on the core cluster identified on the image, this cluster is large enough and has a level of interconnection to achieve resilience and persistence. The core cluster contains 9,719 accounts. If the outlying groups are removed, this number goes down to 6,826 accounts connected by 17,713 author / retweeted relationships. In this group, 575 accounts were retweeted at least once by five or more other users. Of accounts who are retweeted at least once, the average number of users that retweeted them was 12.7 (with a median of 3). This indicates that while there are some particularly influential accounts, much of the distribution occurs through a broad network of interconnected accounts.

This observation is further borne out by the metrics produced by social network analysis, which also show in greater depth the roles key actors play in the network.

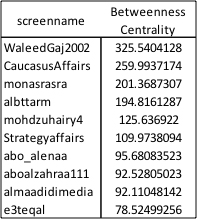

Important findings from this approach include that the counter messaging is much more centralised around a couple of accounts. In contrast, the decentralised dissemination of Jihadist content – the swarmcast – means a range of accounts are reaching different communities, with sufficient levels of redundancy to allow information to continue flowing despite the suspension of some accounts.

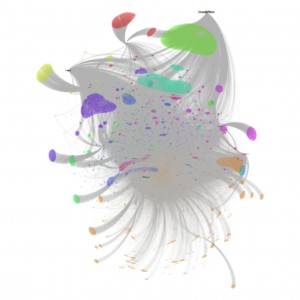

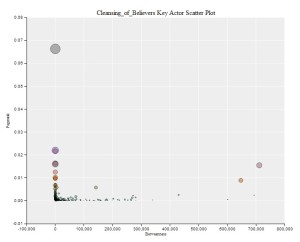

This combination allows the swarmcast to maintain a persistent presence and reach communities which the Counter effort does not. This analysis using the network metrics, confirms the visual analysis from the network image and is also supported by the Key Actor graph. The Key Actor graph and specifically the horizontal spread of accounts shows that a relatively large number of accounts were important in the distribution of information to specific communities.

click to enlarge (interactive)

click to enlarge (interactive)

The combination of analyses and metrics produced by social network analysis, confirms findings from earlier studies, that the media mujahedeen distributes content rapidly, through a resilient network capable of reconfiguring when some accounts are suspended.

#opISIS:

There have been repeated stories over the last year of jihadist accounts being suspended, including in the aftermath of the beheading of James Foley, or the attempts by hackers linked to Anonymous to disrupt accounts as part of Operation No2ISIS.

On 6th February an article posted on Counter Current News claimed Anonymous had just “destroyed months of recruiting work for the terrorist network known as ISIS” and listed the accounts which they now claimed to control. The article also contained a video which describes the actions and rationale of the Anonymous RedCult team as part of #OpISIS.

click on the image for the video on YouTube

click on the image for the video on YouTube

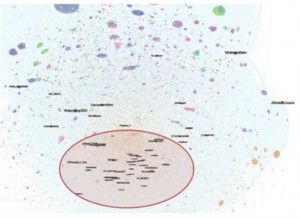

It is unclear how accounts are being selected as part of #OpISIS. However, when comparing the list of accounts that had been hacked, posted on the 6th February and comparing it to the users tweeting about #شفاء_الصدور – none (zero) of the users in the original list were involved in the release of the Cleansing of Believers’ Chests.

An updated list posted on the 9th February, listed over 700 accounts. Only 3.1% of those identified as priority targets with over 10 thousand followers appeared in the network of users disseminating the #شفاء_الصدور video. However, of all the accounts posted in the Feb 9th update, around 9.3% of these users were part of the dissemination of the Cleansing of Believers’ Chests.

Given the dispersed nature of the network and the relatively small proportion of users who were affected by #OpISIS and had been disseminating #شفاء_الصدور, the Jihadist swarmcast continues to exhibit speed and resilience. This allows the ‘media mujahedeen’ and those sympathetic to ISIS to maintain a persistence presence for their content online.