The Propaganda of Jihadist Groups in the Era of Covid-19

Since the very beginning of the pandemic, jihadist groups have been addressing and discussing the issue of Covid-19 in their propaganda, seeking to interpret it for their constituencies and exploit it for their cause. As we shall see in detail below, these groups have sought to use the pandemic as an opportunity to denigrate their enemies, spur recruitment, and inspire attacks. They have also tried to cast the pandemic as a warning from Allah to mankind, including Muslims, and in many cases have detailed strategies for preventing the virus’s spread.

Jihadist messaging regarding the pandemic has not been uniform, however, as the following survey of the different groups’ propaganda will show.[1] The main difference is seen between those groups focused more on stopping the spread (e.g., the Taliban, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham) and those focused more on exploiting the pandemic to stoke violence and amplify their message (e.g., the Islamic State, al-Qaida). All of these groups, however, have benefited from one of the main effects of the pandemic, which is the considerable increase in time spent on the internet and social media as people were forced to isolate themselves at home. To that extent, the pandemic has created fertile ground for jihadist propaganda and proselytising campaigns.

The Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP)

Among the first groups to speak publicly on the issue of Covid-19 was the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), a Uyghur jihadist organisation with links to al-Qaida.[2] In a video published in February 2020 on the Islam Awazi media channel, titled “The Perspective of the Mujahedeen Regarding the Corona Outbreak in China,” the TIP states that the outbreak in China is a “punishment from Allah” for the Chinese oppression of the Uighur minority in Xinjiang: “They destroyed mosques and turned them into places of dancing, vice and insolence, they trampled on the Koran and burned them, transgressed honour and raped women […] God’s vengeance came against these criminals and sent them the deadly coronavirus […] the whole world knows that what happened in China, is simply part of God’s punishment.” In the video, the group gives an overview of the pandemic and rebukes the Chinese state for allowing the consumption of “meat forbidden by the Quran.” The TIP video ends with the spokesman’s hopeful statement that the pandemic will lead to the destruction of the atheistic Chinese state.

The Islamic State

The Islamic State has addressed the issue of Covid-19 in several statements, not explicitly naming the Coronavirus or the term Covid but rather speaking about pandemics in general.

The first statement, an infographic titled “Sharia Guidance for Managing Pandemics,” was published in the second week of March 2020 in issue 225 of the weekly newsletter al-Naba’. The infographic cites various hadith to emphasize hygiene and other precautionary measures regarding contagious diseases. The advice for militants includes instructions to “cover your mouth when yawning and sneezing” and to “wash your hands.” The infographic also warns healthy militants not to go to countries affected by the pandemic and those who are sick not to travel. At the same time, it reminds the militants that the pandemic is ultimately under the control of God, stating that “it is necessary to believe that diseases are not infectious on their own but are by Allah’s command and decree,” and it further emphasizes the necessity of “relying upon God and seeking refuge in him to be spared from disease.” Soon after, during the same month, the Islamic State published a 2-minute-and-13-second video reiterating the same guidance as the infographic. In both the infographic and the video, the lettering and banners are either purple or green, purple indicating a hadith of the Prophet and green indicating advice of a hygienic nature.

The Islamic State would return to the subject of the pandemic in issue 226 of the al-Naba’ newsletter, which was published on March 19, 2020. The issue included a lengthy editorial on the spread of the contagion showing how the organisation was seeking to exploit the pandemic in service of its strategy. The editorial makes a number of points about the nature and implications of the pandemic and how the mujahideen ought to go about exploiting it:

- The pandemic is an example of Allah’s torment, which strikes especially at idolatrous nations and unbelievers.

- The Crusader (i.e., Western) nations are concerned about the current and potential consequences for the economy, including the prices of goods and services.

- The Crusaders face pressure on their military deployments abroad at a time when they have been trying to bring their troops home. There is also the fear that with the pandemic come terrorist attacks in their own countries.

- The Crusaders hope that the mujahideen will not carry out attacks even as they feign ignorance of their own crimes against Muslims; the latter should feel no sympathy for unbelievers and apostates but should seize the opportunity to free Muslim prisoners from the prison camps in which they suffer terribly.

- Muslims should also remember that obedience to Allah allays His torment and wrath, so performing jihad and striking enemies is the best way to protect oneself from the pandemic.

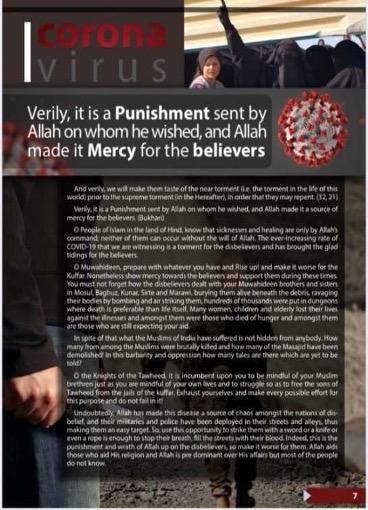

The following week, the Islamic State’s propaganda again took up the matter of Covid-19, this time with a twist. In the editorial of al-Naba’ issue 227, the group talked almost exclusively about the United States, casting doubt on the United States’ ability to deal with global events, to contain the pandemic, and otherwise to anticipate risks and protect itself. Also in February, the English-language magazine The Voice of Hind, associated with the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Hind, or Hind Province, devoted a page to the pandemic. The brief editorial, titled “Verily, it is a Punishment sent by Allah on whom he wished, and Allah made it Mercy for the believers,” echoes many of the Islamic State’s earlier points, including the idea that the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on non-Muslim countries and the importance of seizing the opportunity to attack enemies. “The ever-increasing rate of COVID-19 that we are witnessing,” reads the editorial,

is a torment for the disbelievers and has brought the glad tidings for the believers. O Muwahideen, prepare with whatever you have and Rise up! and make it worse for the Kuffar […] Allah has made this disease a source of chaos among the nations of disbelief, and so their military and police have been deployed in their streets and alleys making them an easy target. So use this opportunity to strike them with a sword or a knife or just a rope to stop their breathing, fill the streets with their blood.

For the Islamic State, then, Covid-19 was at this stage a welcome development since it was seen as mainly affecting unbelieving nations and possibly providing additional incentive to wage jihad. There was some concern about the spread of the virus among Muslims, as the first Islamic State publications on the subject stressed mitigating measures drawn from prophetic guidance. But for the most part the group’s tone was one of optimism and schadenfreude.

In the same period, several unofficial pro-Islamic State media channels published posters and messages on various platforms recalling and reiterating the information previously spread by the organisation on its official channels, including the theme of divine punishment of the unbelievers and the idea of the virus as being the will of Allah. Among the most active of these channels were “Coronavirus: A Soldier of Allah” and “GreenBirds” on the Rocket.Chat platform.

The Taliban

The Taliban’s approach to the pandemic has been quite different from the Islamic State’s, the group’s leadership being concerned above all with stopping the spread of the contagion in Afghanistan, particularly in government prisons where thousands of Taliban militants were being held. In a statement issued on 3 March 2020, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid expressed dismay at the rapid spread of the virus, stating that the blame for infections and deaths “will be the responsibility of the Kabul government and its foreign supporters.” The group has since repeatedly issued security guidelines to counter the spread of the virus and has asked all Afghans returning to the country from abroad to have themselves tested.

On March 18, 2020, the Taliban’s official website, “Voice of Jihad,” published a “Statement concerning the fight against coronavirus” in which the group mixed religious observations about the nature of the virus with practical recommendations about how to fight it and protect people from it. “The Coronavirus is a disease ordered by Almighty Allah because of disobedience and sins of mankind or other reasons,” the statement read. “According to the directives of the scholars, people should recite effective prayers frequently and increase the reading of the Holy Quran, give alms and charity and turn to Allah in repentance for their past sins. […] In addition, safety guidelines issued by health organisations, doctors and other health experts should be adhered to and all safety precautions should be followed to the best of their ability.” Since the end of March 2020, the Taliban have refrained from offering such religious assessments of the pandemic, rather issuing rules and regulations to help counteract it.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani Taliban, or Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which presents itself as a subsidiary of the Afghan Taliban, has promoted the theory that the Jews and their allies were secretly behind the pandemic. The eighth issue of the Urdu-language magazine Mujalla Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, published in December 2020, includes an article by mufti Abu Misbah titled “The Coronavirus and the Background Realities,” in which “the Jews and their puppets” are blamed for releasing the coronavirus in order to harm Muslims. According to this conspiracy theory, the virus was developed in the 1960s by a Scottish virologist, and afterwards “the COVID-19 virus was kept in a safe place and properly concealed so that it could be used as an atomic bomb, especially against Muslims.” It was released as part of “the work of those dreaming of establishing […] a Jewish superpower government.”

Al-Qaida

As for al-Qaida, which, like the TTP, bills itself as a jihadist entity subordinate to the Afghan Taliban, the group’s propaganda has focused on several themes, from the importance of hygiene and cleanliness to the idea of the pandemic as being the just rewards of the unbelievers.

The first remarks by al-Qaida on the subject, published in March 2020, took the form of a six-page statement by al-Qaida Central’s al-Sahab Media titled “The Way Forward: A Word of Advice on the Coronavirus Pandemic.” In the statement, both the Islamic world and humanity at large are described as having invited the pandemic by means of their wicked behavior. “It must be said,” the statement reads, “that the arrival of this pandemic to the Muslim world is only a consequence of our own sins and our distance from the Divine methodology.” Several pages later it affirms that “this pandemic is a punishment from the Lord of the Worlds for the injustice and oppression committed against Muslims specifically and mankind generally.” The statement also takes the opportunity to invite Westerners to embrace Islam in light of the evident failure of their societies to stop the pandemic, a failure that is attributed to “your usury-based economy.” As the pandemic has revealed, “Your governments and armies are helpless, utterly confused in the face of this weak creature. Allah (swt), the Creator, has revealed the fragility and vulnerability of your material strength.” From there the al-Qaida statement turns to the issue of hygiene, noting how “Islam places great emphasis on the principles of prevention to protect against all forms of disease. This is implemented through a system of personal hygiene that takes the form of a regular routine that is repeated several times throughout the day.” The statement concludes on an optimistic note, addressing the Crusaders, Zionists, and apostates by saying, “The fear and panic that has befallen you bodes well for us, and we ask Allah to hasten your fate.”

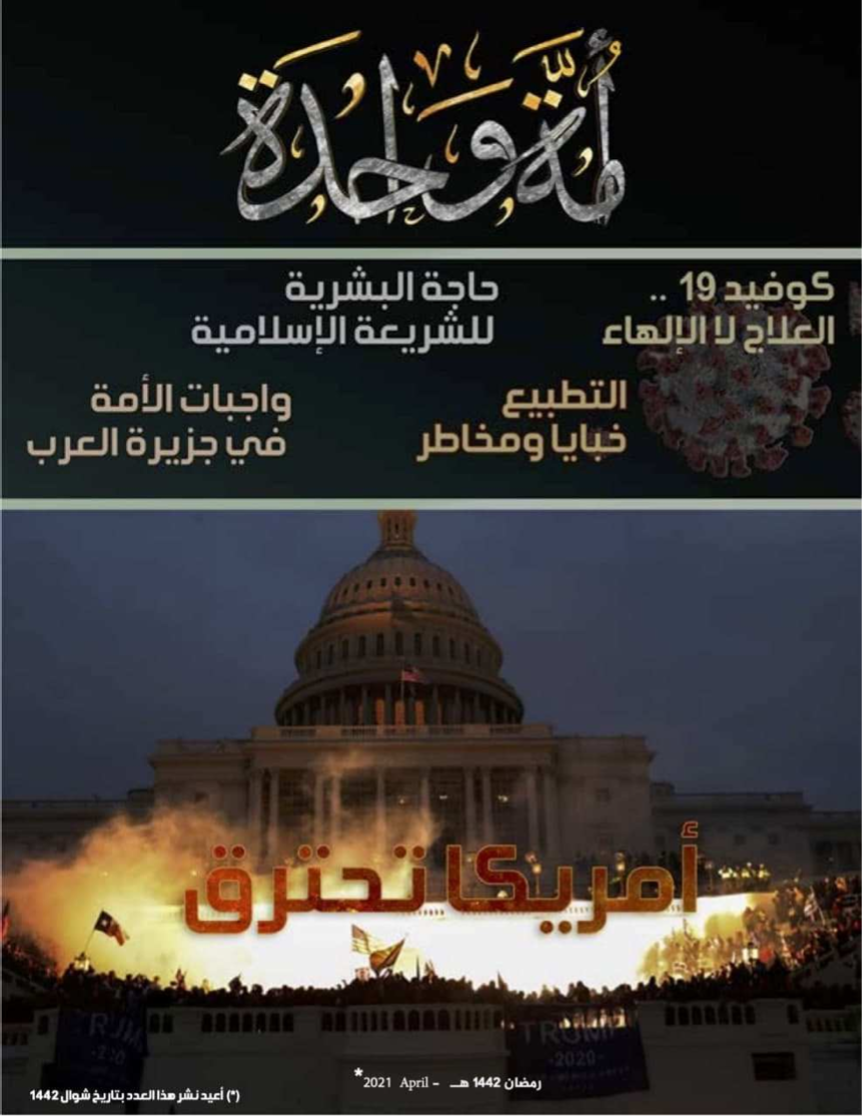

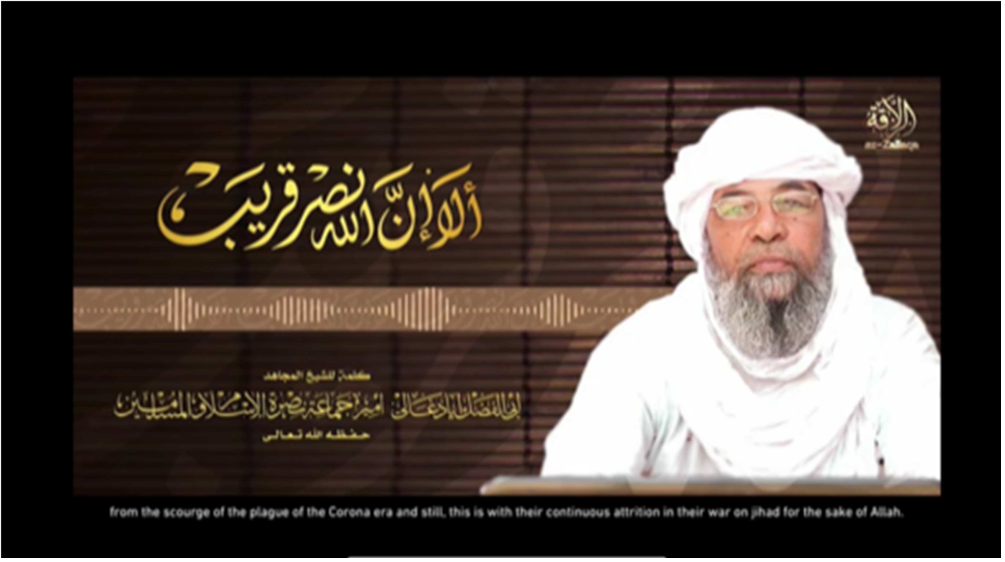

Subsequent statements by al-Qaida and affiliated groups have tended to focus on the devastating effects of the pandemic on the West and the opportunities created for terrorist attacks. In April 2021, al-Qaida Central’s flagship magazine, One Ummah, devoted an issue to the subject of “America Burns.” The opening article exulted in the economic, political, and social hardships facing the United States due to Covid-19, noting that the number of deaths in America from the pandemic has crossed the half million mark. Joe Biden is quoted calling the distribution of the vaccine under the Trump administration “a catastrophic failure.” Several months later, in August 2021, Iyad Ag Ghali, the leader of the Sahelian al-Qaida affiliate Jama‘at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin, appeared in a video that touched on the pandemic and its effects on the United States. In the video, Ag Ghali states that “what is happening to its [France’s] master, America, scourged by the Corona plague era […] this is because of their continuous attrition for their war on jihad.”

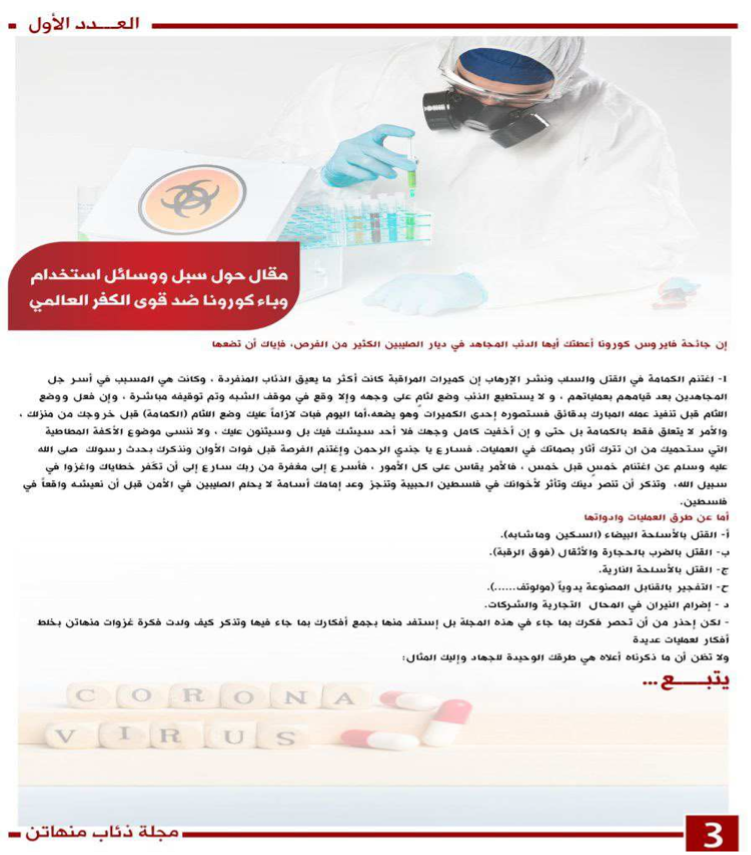

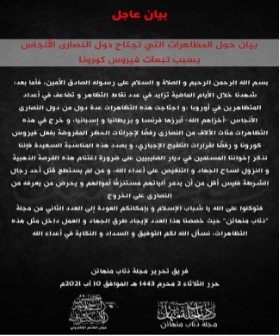

The previous year, in November 2020, the pro-al-Qaida media group al-Malahem Cyber Army published the first issue of its new Wolves of Manhattan Magazine, calling for attacks to exploit the complex security situation created by the pandemic. Lone attackers were encouraged to disguise themselves with masks (so as not to be identified) and to kill and injure enemies by poisoning the stocks of face masks. The following year, in August 2021, al-Malahem Cyber Army again sought to promote attacks in the new Covid environment, publishing a statement on anti-lockdown demonstrations in the West. The demonstrations, according to the statement, were a “golden opportunity” for the Muslims to attack “the enemies of God,” particularly the police. Those unable to kill a policeman, it added, can at least destroy their vehicles.

Al-Shabaab, al-Qaida’s affiliate in Somalia, has issued statements both exulting in the damage done by the pandemic to the West and providing guidance on how militants and those under al-Shabaab’s authority can protect themselves. In May 2020, the group announced the creation of a special committee of doctors, scientists, and local officials to manage the response to Covid-19 in the territories under its control. In March 2021, al-Shabaab warned in a statement against the Astrazeneca vaccine, the vaccine that was being distributed by “the apostate Somali regime.” The warning came not because of anti-vax sentiment but rather because of the alleged “ineffectiveness and adverse side effects” that had led a number of European countries to suspend the administration of the vaccine. “Do not allow your children and family members to be used as guinea pigs in the race to develop a potent vaccine for the coronavirus pandemic,” the statement advised, suggesting instead that Muslims “adhere to the medications prescribed in the Qur’an and Sunnah of the Prophet (peace be upon him), such as black seed and honey […] Until a safe and effective vaccination becomes available, the Office of Politics and Wilaayaat urges the Muslims of Somalia to repent and supplicate to Allaah in order to alleviate their suffering and uplift them from the disease.”

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham

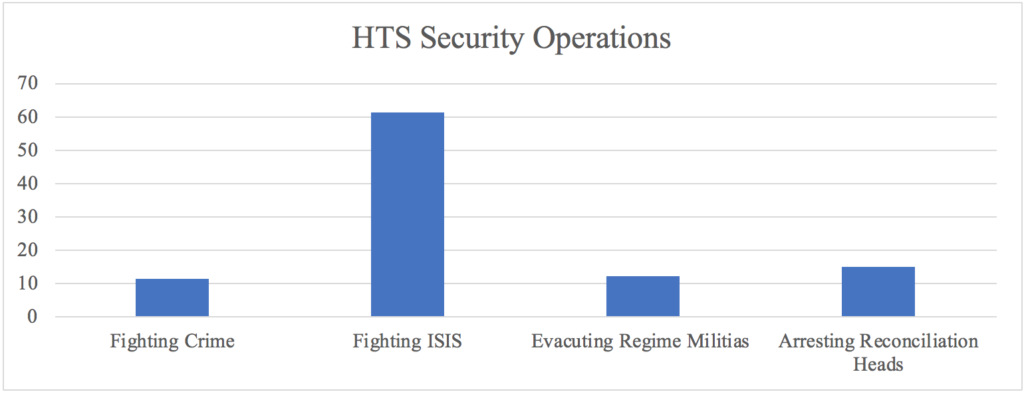

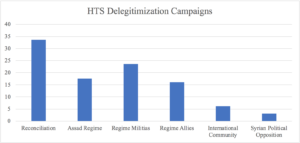

Like al-Shabaab, the Syrian jihadist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which was once affiliated with al-Qaida but has since become independent and now holds territory in north-west Syria, has been focused on preventing the spread of Covid-19 in its propaganda. While boasting in one statement that the virus has killed some of those who have “killed and shed the blood of the Muslims all over the world,” most of HTS’s attention has been devoted to emphasizing anti-Covid measures. In one poster released by HTS’s media outlet, al-Ebaa, Syrians in HTS-controlled territory are instructed to wear masks, wash their hands, and refrain from touching their faces, among other measures.

Conclusion

Jihadist organisations have devoted a great deal of attention to the Covid-19 pandemic in their propaganda. For the most part, however, this has had little favourable impact on the operations of jihadist groups. Jihadist activity has not significantly declined in the era of Covid-19, but neither has it increased dramatically either. The most that can be said is probably that increased time spent on the internet and social media has been conducive to greater radicalisation and recruitment. Jihadist organisations have sought to use the pandemic as an opportunity to strengthen themselves but do not seem to have achieved the desired result. Strategically, perhaps, only the Taliban and HTS have been able to exploit the pandemic operationally, providing governance services, medical aid, and infrastructure improvements in the territories they control, thus improving their credibility and popularity and demonstrating that they are more capable and prepared to meet the challenges of Covid-19 than the governments in Kabul and Damascus. In this way, jihadist organisations have sought to present themselves as a viable alternative to established governments, again showing that their aims are not limited to perpetrating violence alone.

[1] The images and statements included in the analysis were retrieved directly by the author while monitoring jihadist media channels. Where possible, links to sources are provided for researchers who wish to view or further investigate the material.

[2] The TIP has mainly been operating in Syria in recent years. See more at https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2018/07/analysis-the-turkistan-islamic-partys-jihad-in-syria.php.The Syrian branch of the TIP has collaborated with HTS and Abu Muhammad al-Jolani. In recent months there seems to be a split within the Syrian branch of the TIP (due to the choice of a part of the militants and leaders to participate in the fight of HTS against the other jihadist groups operating in the Syrian theatre). Many leaders and militants who disagree with the line adopted by HTS seem intent on moving towards the TIP strongholds in Afghanistan.