Nico Prucha

August 20, 2013

In this part of our series for Jihadica on the Jihadi Twitter phenomenon, Ali Fisher and Nico Prucha take a closer look at 66 Twitter accounts recommended by a Jihadi online forum user.

To be clear, we are analyzing these accounts that are defined in this posting as most important for jihadi sympathizers, but it does not necessarily mean that the individual Twitter accounts are an integral part of this worldview.

A posting on the Shumukh al-Islam forum recently provided a “Twitter Guide” (dalil Twitter). This ‘guide’ outlined reasons for using Twitter as an important arena of the electronic ribat; identified the different types of accounts which users could follow; and highlighted 66 users which Ahmad ‘Abdallah termed “The most important jihadi and support sites for jihad and the mujahideen on Twitter”.

We mentioned this guide in our first post kicking off the series on Jihadica. In this post we intend to clarify the meaning of Ahmad ‘Abdallah’s Twitter guide, published at end of February 2013 on Shumukh al-Islam. We will then analyse the data on the twitter accounts which he claimed to be the most important within the overall jihadi context. An overview of this data is also available in our infographic, 66 Important Jihadis on Twitter (click here or the image for the full size):

In both this post and the infographic we have used ‘Jihadi Accounts on Twitter’ as shorthand for those named in the unwieldy ‘the most important jihadi and support sites for jihad and the mujahideen on Twitter’. It is not the intention of this post to discuss whether, or not, the 66 users should be considered jihadis, but to identify the accounts recommended in the guide to using Twitter in the jihadist context, recommend in the forum thread.

Twitter as the “electronic ribat”

Twitter, for Ahmad ‘Abdallah, has an important role as an electronic ribat. Following a classical rhetoric and it’s comprising meaning, Ahmad ‘Abdallah terms “Twitter one of the arenas of the electronic ribat, and not less important than Facebook. Rather, it will be of much greater importance as accounts are rarely deleted and its easier to get signed up”, without providing a phone number as ‘Abdallah writes. The advantage is that you can follow anyone without having to be accepted as a friend as on Facebook, but “you will see all of their postings just as on Facebook.”

A note on the term ribat in contemporary jihadist mindset

To translate and conceptualise the Arabic term ribat can be very contentious. The term is frequently referred to in both jihadist videos and in print literature in the context of religiously permissible warfare; in a modern meaning it could loosely be translated as “front”.

Ribat is prominent due to its reference in the 60th verse of the eight chapter of the Qur’an, the “Surat Al-anfal” (“the Spoils of War”). It is often used to legitimise acts of war and among others found in bomb making handbooks or as part of purported theological justification in relation to suicide operations. Extremist Islamists consider the clause as a divine command stipulating military preparation to wage jihad as part of a broader understanding of “religious service” on the “path of God.”

Ribat as it appears in the Qur’an is referenced in the context of “steeds of war” (ribat al-khayl) that must be kept ready at all times for war and hence remain “tied”, mostly in the Islamic world’s border regions or contested areas. In order to “strike terror into [the hearts of] the enemies of Allah” (Ahmed Ali), or “to frighten off [these] enemies of God” (see below), these “steeds of war” are to be unleashed for military purposes and mounted (murabit – also a sense of being garrisoned) by the mujahidin.

The relevant part reads, according to the translation by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem:

“Prepare against them whatever forces you [believers] can muster, including warhorses, to frighten off [these] enemies of God and of yours, and warn others unknown to you but known to God. Whatever you give in God’s cause will be repaid to you in full, and you ill not be wronged.” (8:60).

Ribat has two main aspects in contemporary jihadist thinking. First, the complete 60th verse of the Qur’an is often stated in introductions to various ideological and military handbooks or videos. While some videos issue ribat in connection with various weapons and the alleged divine command to “strike terror into the hearts of the enemies.”

In the past years, the ribat has migrated and expanded into the virtual “front”, as the murabit who is partaking in the media work has been equated with the actual mujahid fighting at the frontlines.

Types of account important for jihad and the mujahideen on Twitter

As the Twitter ‘guide’ states;

“Today I have summarized for you all of the renowned accounts in support of jihad and the mujahideen that convey their news or are in their favour; some are official accounts [by jihadi groups or brigades], some of which are accounts by scholars, ideologues, and supporters. We ask you for your support, even if just by following them.” In general, Ahmad ‘Abdallah lists five different types:

– “Accounts by Media and News Foundations” referring to all Twitter accounts maintained by the official jihadi media outlets such as Fursan al-Balagh li-l i’lam (@fursanalbalaagh) or the Ansar al-Mujahideen Forum (@as_ansar).

– “Accounts by Scholars and Writers” meaning stars such as the London-based Hani al-Siba’i (@hanisibu) or Muhammad al-Zawahiri (@M7mmd_Alzwahiri) or the notorious Abu Sa’d al-‘Amili (@al3aamili), to list a few.

– “Accounts by members of jihadist forums and brothers and sisters supporting the mujahideen.” This is a good example of ‘hybrid’ users, active inside the jihadi forums and social media. These accounts operate independent of the forums and remain active even when the forums are down – this means that there is no gap and no disruption of jihadi content being disseminated when the forums should be down or out.

– “Accounts supporting the mujahideen in Syria (al-Sham al-‘izz wa-l-jihad)”. This includes media activists in support of prisoners (@alassra2012) and campaigns by the Ansar al-Sham (@7_m_l_t) a charity regularly requesting money and support (financial, logistical, personnel) in general.

– “Various accounts”, this section includes activists such as the “unofficial account of Minbar al-Tawhed wa-l-Jihad” (@MinbarTawhed); Israeli Affairs (@IsraeliAffairs); or the high profile account Mujhtahid, “the divulging secrets of the Al Salul” an insulting reference to the ruling Saudi family (@mujtahidd).

The posting is concluded with the signature “Abu ‘Abdallah al-Baghdadi” and his own twitter account (@Ahmed_Abidullah).

“The most important jihadi and support sites for jihad and the mujahideen on Twitter”

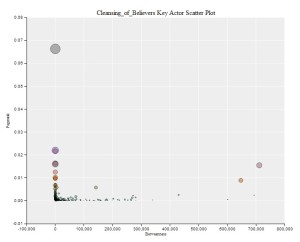

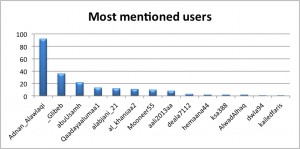

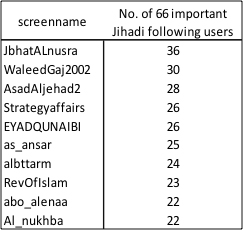

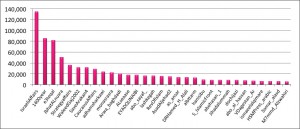

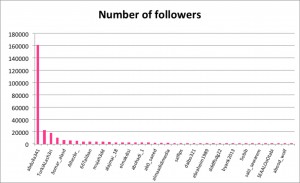

We took the profile data for the 66 accounts listed by Ahmad ‘Abdallah to discover who these important users are individually and what we could find out about them as a group. One of the first elements in the data users tend to look at is the number of followers an account has. While not a measure of influence, it does give an indication that users have heard of the account and that they may be interested in seeing more of their content.

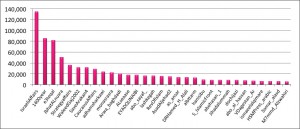

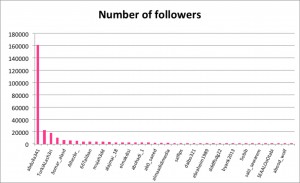

Of the important jihadi, identified by Ahmad ‘Abdallah, @mujtahidd – has over a million followers, but this an exception, next most followed are @IsraeliAffairs – around 180,000 followers – and @1400year – around 30,000 followers.

Who are these users?

Mujtahid is an Islamic term of jurisprudence, a “legist formulating independent decisions in legal or theological matters, based on the interpretation and application of the four usul”, according to Hans Wehr. It can also simply mean “industrious, diligent.”

His bio on Twitter merely consists of two Arabic names, Harith and Hummam, and his email (mujtahidmail@gmail.com). The two names also serve as a code relating to the saying of prophet Muhammad who stated these two names as of the most dear ones to God and to him (besides ‘Abdallah and ‘Abd al-Rahman). Hummam means lion and Harith cultivator. As location he simply entered: The world.

Some Twitter members claim that @mujtahidd is a “known whistleblower inside the #Saudi government”.

@IsraeliAffairs – has about 180,000 followers and is the next most followed account,

in his bio, he writes:

“I am Muslim, my citizenship is Arab, I work on behalf of my country which is every span of hand on earth; raising on it the Adhan [the call to prayer]! [I am] diplomat, translator, researcher in Israeli affairs…”

@1400year – has about 85,000 followers, the third most followed account.

The Arabic name of this account is gharib fi wadanihi – “the stranger in his own country”; the sentiment of gharib is a reference to a mental passageway as the ‘true’ believer considers himself somewhat as a foreign object in this world, associating oneself to the early Muslims who had been perceived as such strangers in their historical context by their social environment. Stranger or estranged is used here in the context of Palestine and the Israeli occupation.

When the data was captured for this post his bio stated:

“The man in the picture is Rachid Nekkaz, a French millionaire of Algerian origin, who opposes France’s ban of the niqab. He said to the Muslimat of France to wear the niqab and I will pay the fine, I am honored by placing his picture [on my account].”

His updated bio, however, as shown in the screen grab above, states:

“The demise of Israel may be preceded by the demise of [Arab] regimes that made a living on the expense of their own people, laughing at them, destroying the societies (…).”

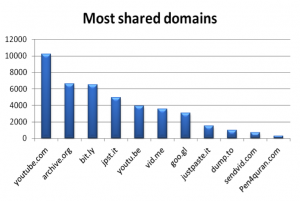

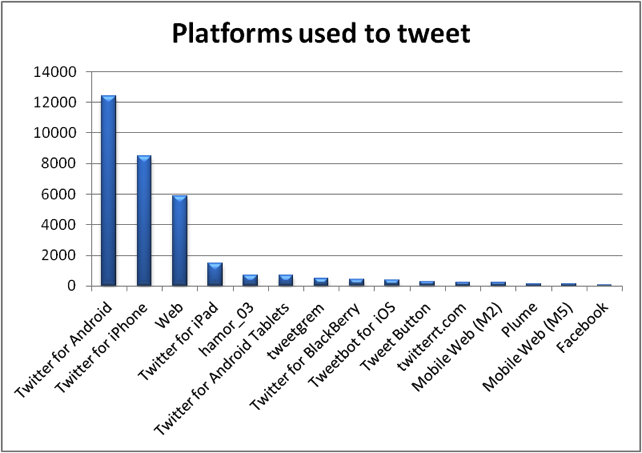

@1400year also has a YouTube account with 1,830 subscribers and 437,243 views. The links across platforms allows users to more effectively create their zeitgeist. This is similar to the way jihadist groups such as Jabhat-al-Nusra are using Twitter to disseminate links to video content shot on the battlefield in Syria and posted for mass consumption on YouTube, as we outlined in an article for the CTC Sentinel recently.

Of the remaining accounts, 32 of the 66 accounts listed have between 5,000 and 100,000 followers (click to enlarge):

The mean number of followers is 28,220 but this is heavily influenced by the three accounts with the greatest number of followers. The median number of followers is much lower 5377.

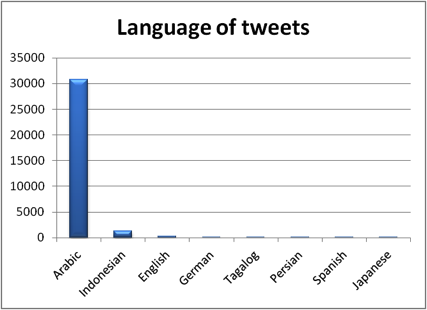

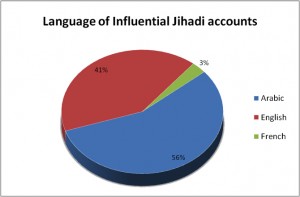

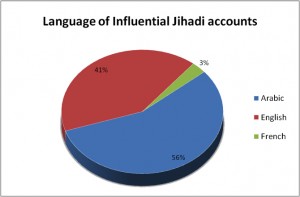

What language do they use?

The majority (56%) use Twitter in Arabic with 41% using English and 3% using French. The language of an account was determined from that listed in the twitter profile data.

Where are the accounts located?

Few users write meaningful locations in the ‘location’ field on their Twitter profile, and fewer still enable geotagging of Twitter content. However, a surprisingly high number of people tend to set the clock in their timezone, to either the correct timezone – or to a timezone in which they would like to appear to be.

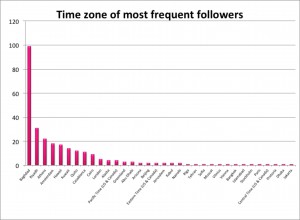

Casablanca was the most common location account holders used to signify their time zone. It does not mean they are in these specific cities but it does provide an indication of the area of the world with which they associate.

Note on why using time zones can be useful:

In short, humans are creatures of habit, they like the clock to show the time – either where they are or with the location with which they mentally associate. For example, following the 2009 Presidential election in Iran, there was a brief campaign for users to show support for the protesters by changing their location to Tehran, perhaps only to confuse Iranian authorities. This strategy had more than a few problems, as Evgeny Morozov pointed out at the time. One of the more notable issues, which is relevant in this context, is the failure of the less savvy Twitter users to change the time zone as well as the location. Another problem with this strategy was the tendency of slacktivists to use different tags, such as #helpiranelection, to those used by protesters or ‘digital insiders’ (#GR88, #Neda, #Sohrab), discussed in detail here. (The activities of slacktivists are discussed by Evgeny Morozov here) As a result, interaction on Twitter was predominantly characterised by a series of local conversations rather than a one global debate, an issue discussed in greater detail here.

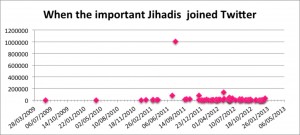

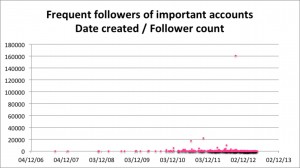

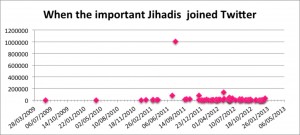

When did the important jihadi accounts join Twitter?

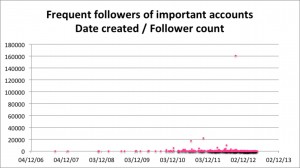

Although one jihadi account has been active since 2009, many of the important jihadi accounts were created during 2012. This data echoes the shift away from discussion on forums and toward social media, lamented by Abu Sa‘d al-‘Amili in his recent essay on the state of global online jihad (discussed here).

The data also shows little tendency for accounts that have been active for a long time to have more followers than those created more recently.

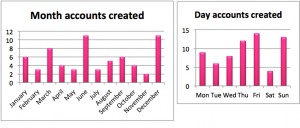

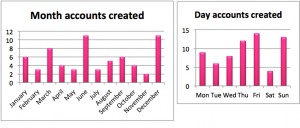

On what day and month did the most important Jihadi accounts for Ahmad ‘Abdallah create twitter accounts? This data indicates Friday, though Thursday and Sunday are not far behind. Equally, accounts were most frequently created in June and December.

On what day and month did the most important Jihadi accounts for Ahmad ‘Abdallah create twitter accounts? This data indicates Friday, though Thursday and Sunday are not far behind. Equally, accounts were most frequently created in June and December.

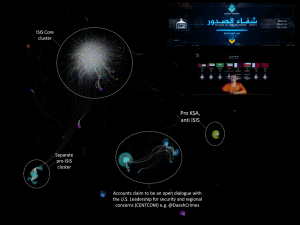

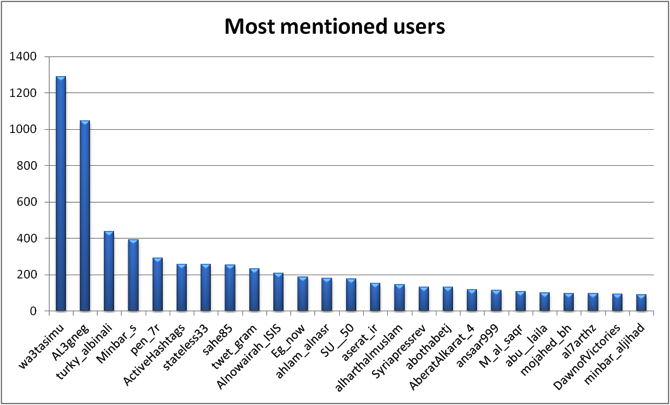

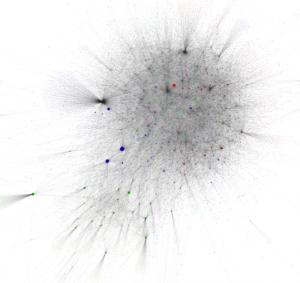

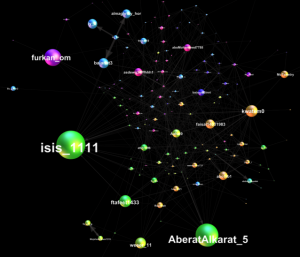

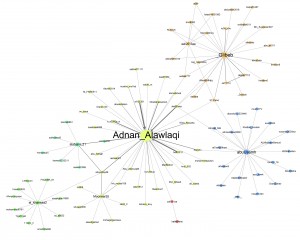

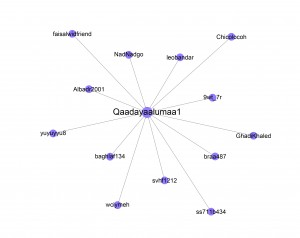

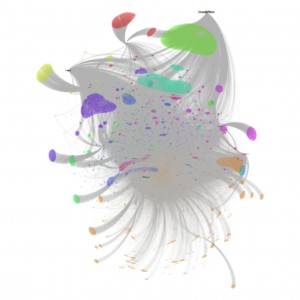

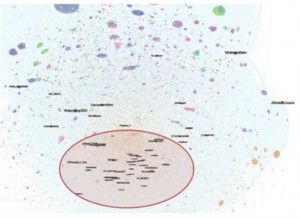

Do these accounts all speak to the same followers?

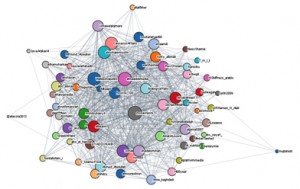

If each of the 66 ‘important jihadi’ accounts were followed by a different group of Twitter users this would mean collectively they were reaching 1.8 million users. However, @mujtahidd alone is followed by over 1.1 million followers, and the real number following the remaining important jihadi accounts is much lower than 700,000. This is because some users follow more than one ‘important jihadi’ account. Using network analysis, we found that the network following one or more of the important jihadi accounts (excluding @mujtahidd) was a little over 370,000 users and 850,000 follower/following relationships.

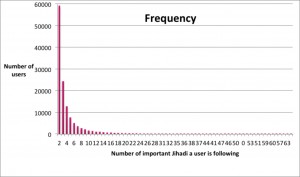

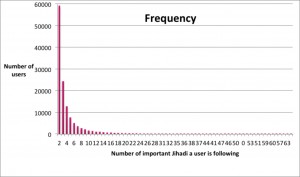

As one may expect from an online social environment, many users follow one or two accounts, while a very few follow many of the ‘important jihadi’ accounts. The graph below demonstrates a close approximation of a ‘power law’ curve (this discussion hints at why power law / logarithmically normal distribution might be a useful way to approximate user ranking).

Of those users who follow on of the 66 important jihadi accounts (minus @mujtahidd), 34% follow more than one important jihadi account. However, of the users which follow more than one important jihadi account, 45% only follow two accounts. These can be thought of as casual followers.

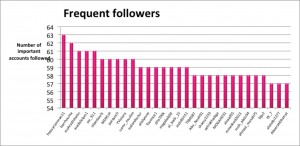

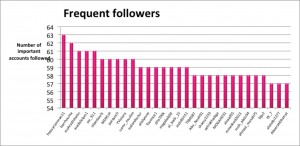

At the other end of the scale there are 109 users who follow fifty or more of the important jihadi listed and 504 users that follow 40 or more. These are the more engaged followers.

Engaged followers of ‘important jihadi’ accounts

Knowing that a user is particularly engaged in following the same accounts as were deemed important in the Twitter guide, does not necessarily indicate any political affiliation – not least because of the number of CT scholars actively following these accounts (and perhaps some of those using Quito / Hawaii as a time zone).

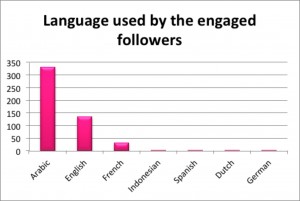

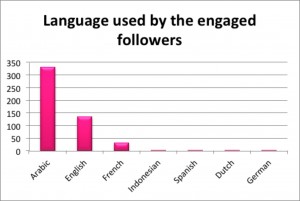

It is however, instructive to consider the aggregated traits of the group as a whole, for example, of the 504 users who follow forty or more important jihadi accounts, what language do they use?

Unsurprisingly given the dominant languages used by important jihadi accounts, Arabic, English and French are the most frequently used languages. In addition, there are a small number of users who use Twitter in other languages, Indonesian, Spanish, Dutch and German.

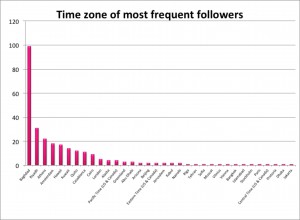

From the aggregated profile data, a similar question can be asked about where in the world these engaged users appear to be.

Using the location users have designated to set time on their twitter account, the cultural importance of appearing (at least) in the Arabian Peninsula. Similar to the data on the 66 ‘important jihadi’ the engaged followers tend to have most frequently created accounts in 2012, equally, apart from a small number of exceptions, these users each have a small number of followers.

What does this tell us?

What does this tell us?

The ‘important jihadi’ accounts, as one may expect, tend to tweet in Arabic. They are followed by a network of around 300,000 people (if @mujtahidd is excluded) most of whom are casual observers.

There are, however, somewhere between 500 and 1000 more engaged followers. These users tend to be Arabic speaking, have created accounts in the last year to 18 months, have relatively few followers and appear to have a greater tendency to identify with the Arab peninsular than the 66 ‘important jihadi’ accounts.

In a follow-up post we’ll look at the network of the 66 ‘important jihadi’ accounts to see if there are groups within the 66 which tend to follow each other. This may reveal a relatively dense network indicating a high degree of mutual awareness within the network. On the other hand, it may reveal a sparse network, which could indicate a low awareness of each other, a decision not to follow other users on twitter – reflecting a use of twitter as a ‘broadcast’ mechanism, or that while the Twitter guide indicated the account as important within the jihadi context, the user actually has other interests, affiliations or tendency to establish follower relationships with users outside what Ahmad ‘Abdallah thought of as the jihadi context.