Aaron Zelin

February 18, 2020

Many within Syria viewed Tunisians as more extreme relative to other foreign fighters.[1] There is a twofold aspect to this. The first relates to the human rights violations that Tunisians have been involved in within Syria, which is not necessarily unique considering all of the human rights violations committed by members of IS, whether local or foreign. The second, which this article focuses on, relates to some Tunisians involved within an extremist trend within IS called the al-Hazimiya (Hazimis), which is named after the progenitor of the ideas these individuals follow, Ahmad Bin ‘Umar al-Hazimi, a Saudi religious scholar. It should be noted that al-Hazimi is not a member or affiliated with IS; his ideas, however, were co-opted by some members of IS. As former Saudi ISIS member Sulayman Sa‘ud al-Suba‘i noted about this extremist trend among Tunisians in ISIS, “it was mostly the Tunisians who were involved in takfir, although personally, I doubt they had such extensive religious knowledge.”[2]

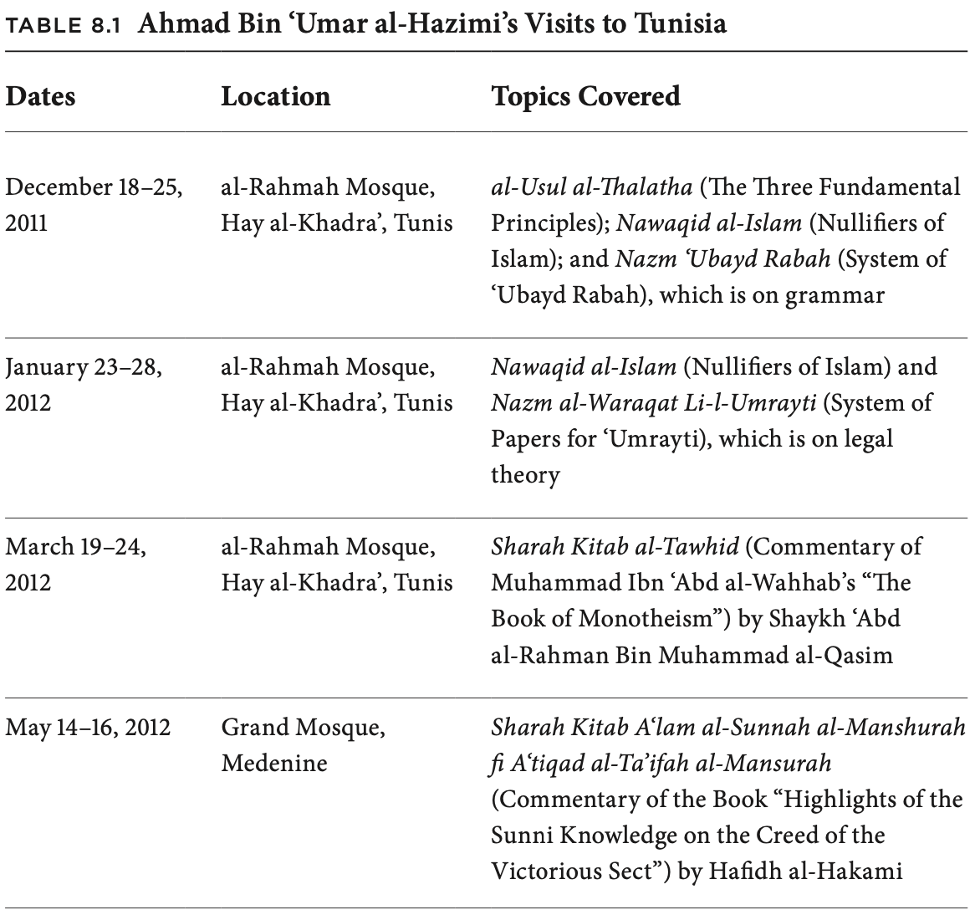

Although some in the Tunisian jihadosphere, especially those that are pro-AQ, claim that the spread of this trend among Tunisians is a consequence of the Tunisian government attempting to sully and divide the Tunisian jihadi movement, it is a bit more complicated than that.[3] As background, al-Hazimi did four different lecture series in Tunisia between December 2011 and May 2012 (see table 8.1) with the local jihadi milieu. Interestingly, the first series was announced on October 25, 2011, a mere two days after the Tunisian Constituent Assembly election, which al-Nahdah won as the leading political party.[4] Al-Hazimi’s first three visits to Tunisia were in coordination with and sponsored by the Hay al-Khadra’ Mosques Committee and the Islamic Good Society in Tunis. The committee was headed by Abu Muhanad al-Tunisi, who was a senior cleric in AST [Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia] and also ran the al-Rahmah Mosque in Hay al-Khadra’, a neighborhood in Tunis.[5] The al-Rahmah Mosque became an AST-run mosque following the 2011 revolution.[6] Abu Muhanad’s first lecture promoted by AST at the al-Rahmah Mosque noted that it “is where the organization of the two previous sessions with Shaykh Ahmad Bin ‘Umar al-Hazmi” took place since it happened in mid-February 2012.[7] As for the Islamic Good Society in Tunis, in May 2014, the head and some of its members were arrested for money laundering and terrorist financing.[8] This could suggest that this charity was involved with more than just spreading its interpretation of Islam, but with assisting individuals involved in terrorism or helping finance travel abroad to Syria as well. Al-Hazimi’s final lecture in Tunisia was at the Grand Mosque of Medenine, a city sixty-five miles northwest of the Tunisian-Libyan border.

Besides these courses, in early March 2012, al-Hazimi helped create and was the supervisor of the Ibn Abu Zayd al-Qayrawani Institute for Sharia Sciences.[9] It was based in Hay al-Khadra’ and was named after the historical Tunisian Maliki scholar. This institute was established in conjunction with the Hay al-Khadra’ Mosques Committee, highlighting its connections to AST as well.

After the institute opened registration on March 10, 2012, there was now a specific institute in Tunisia that was teaching a curriculum that adhered to al-Hazimi’s views on creedal matters (more on this below).[10] This is likely where many Tunisians became exposed to al-Hazimi’s ideas beyond his in-person lecture series or his online presence.

Furthermore, AST promoted Hazimi’s ideas on its official Facebook page via its sharia committee. In December 2012, AST published a list of content that “is obligatory to learn for members of AST” as part of their dawa efforts.[11] AST also republished this list on its official Facebook page as a reminder in mid-January 2013.[12] Besides al-Hazimi’s content, the post suggested Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi’s Democracy: A Religion and The Religion of Abraham as well as a Saudi Arabia Ministry of Islamic Affairs Dawa and Guidance book from 2004 called Accessible Jurisprudence in Light of the Qur’an and Sunnah.[13] The al-Hazimi content contained a six-part lecture series titled al-Usul al- thalatha (The three fundamental principles) exploring the ideas of “Who is your Lord?,” “What is your religion?,” and “Who is your Prophet?”; an eight-part lecture series titled A‘lam al-sunnah al-manshurah fi a’tiqad al-ta’ifah al-mansurah (Highlights of the sunni knowledge on the creed of the victorious sect); and most importantly to the discussion related to extremism within the IS context, a four-part series titled Nawaqid al-islam (Nullifiers of Islam).

The latter lecture is based on a creedal work by the founder of Wahhabism, Muhammad Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, and relates to ten ways that nullify someone from being a true Muslim. In short, the third nullifier says, according to Cole Bunzel, that “one must pronounce takfir (excommunication) on those failing or hesitating to pronounce takfir” in relation to acts of polytheism.[14] Takfir in the jihadi context leads to the legitimization of killing those that fall outside the bounds of their interpretations of Islam. Within this third nullifier is where the shades of takfir between different jihadis, including within IS, is contested. Al-Hazimi believes in the idea of takfir al-‘adhir (excommunication of the excuser), meaning those who follow al-‘udhr bi-l-jahl (excusing someone from the duty of takfir on the basis of ignorance in what they are doing). This, according to those who opposed the followers of al-Hazimi within IS, would lead to a so-called endless chain of takfir. These ideas were thus promulgated in al-Hazimi’s lectures in Tunisia and in the audio series AST posted online for its followers. This negates AQ-apologetic ideologues like Abu Lababah al-Tunisi or al-Maqalaat claiming that the growth in these ideas in Tunisia were a consequence of some conspiracy by the Tunisian government.[15] That being said, it is important to remember that AST’s approach within Tunisia was not takfiri in any manner due to its dawa-first approach. It is clear, however, that these ideas by al-Hazimi did incubate within the minds of some and then were brought to fore more so in Syria once the Tunisian jihadists had joined ISIS/IS. Most notable among these figures was Abu Ja‘afar al-Hatab who had been on AST’s sharia committee.

Based on a reading of al-Hatab’s publications with AST, al-Nahdah’s crackdown upon AST following the government blocking AST from conducting its third annual conference in mid-May 2013 led al-Hatab down this ultra-extreme path. This is because al-Hatab was not writing anything along the lines of takfir al-‘adhir for AST publications. Ahead of the third annual conference, there were signs that al-Nahdah was planning to shut it down, but based on its past behaviors as described in chapter 4 of my book Your Sons Are At Your Service: Tunisia’s Missionaries of Jihad, some within AST likely saw it as a bluff and were not necessarily taking it seriously. Despite these warnings, AST wanted to prepare its followers for the conference, so al-Hatab penned guidance and instruction on how to act. In particular, the third instruction illustrates that al-Hatab was not yet believing in such ultra-extreme ideas. He said, “We need to be humble whether alone or in groups. . . . Our brothers don’t be arrogant especially with your brothers who have not joined AST. They are our brothers in faith. Be humble with them and invite them to attend our annual meeting. Even if they have disagreed with us, they still have the right to guardianship in Islam.”[16]

Only six weeks after this al-Hatab wrote his treatise defending ISIS, saying the only legitimate baya was to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This suggests that the al-Nahdah-led crackdown upon AST, which began in May 2013 and culminated in the group’s eventual designation in August 2013, led al-Hatab to adopt more radical views over time. This was likely reinforced by JN’s [Jabhat al-Nusra’s] challenge to ISIS as well as reinforced once he made it to the war zone context in the summer of 2013. The failed AST experience of a dawa-first approach probably also pushed al-Hatab down a path of no compromise since the softer way did not work in Tunisia. This dynamic was seen with other Tunisians within ISIS too. For example, according to Rania Abouzaid, a Tunisian leader doing a Friday sermon in Syria equated JN’s allegedly softening positions to his experience with al- Nahdah in Tunisia: “He had seen what he termed ‘the reality of these people’ in Tunisia, before his pilgrimage to Syria. ‘They curse God and the Prophet and say it is freedom of expression. They walk around naked and say this is freedom! If you are a Muslim and express your opinion, you are a terrorist! If you call one of them an infidel, they say you are an extremist!.’ ”[17]

Within a year of joining ISIS, al-Hatab and other Tunisians who began to internalize al-Hazimi’s ideas started to run afoul of the group, even though many Tunisians including al-Hatab came into important positions within the organization. For instance, when al-Hatab joined ISIS in the summer of 2013, he was a part of an early version of ISIS’s sharia committee alongside Turki Bin‘ali, who became an arch nemesis of the Hazimi trend within ISIS, and Abu ‘Ali al-Anbari.[18]

Based on my reading of WikiBaghdady, an alleged insider account and leaks on the inner workings of ISIS, which were published between December 2013 and June 2014, the ISIS infighting with JN helped cause the ascendancy of al-Hatab and other Tunisians within ISIS, which allowed for greater space for the Hazimi trend to grow.[19] While some within IS and AQ circles have skepticism about this source, a number of details from these leaks cohere with other information known about IS that has been independently written about since this time period.

In the early stages of the infighting between JN and ISIS, JN arrested two Tunisians, Abu Taj al-Sussi and Abu ‘Umar al-‘Abadi, among others who were not Tunisian, due to their takfiri ways and loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.[20] In line with this, due to the loyalty of Tunisian foreign fighters during the fight with JN, a number of Tunisians were given more senior positions within ISIS, including al-Hatab. As a consequence of ISIS’s violent infighting with JN, which became far more aggressive in January 2014, a number of foreign fighters soured on ISIS because they did not want to fight those they perceived as their brothers in JN, even if there were some political and strategic disagreements. In response, al-Baghdadi nominated al-Hatab to try to stem these losses by receiving new bayat from others who supported the group in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Turkey.[21] Al-Hatab also took charge of attempting to persuade leaders of Syrian rebel factions to defect and join ISIS with a $1,500 incentive; however, this effort allegedly failed.[22] Furthermore, al-Baghdadi placed spies—trusty Iraqis and loyal Tunisians—“with each field commander to fortify ISIS from any defections and have an early notification to try to dissuade the dissidents or liquidate them.”[23] Later on, al-Hatab became an official in IS’s Diwan al-Ta‘alim (Administration of Education).[24]

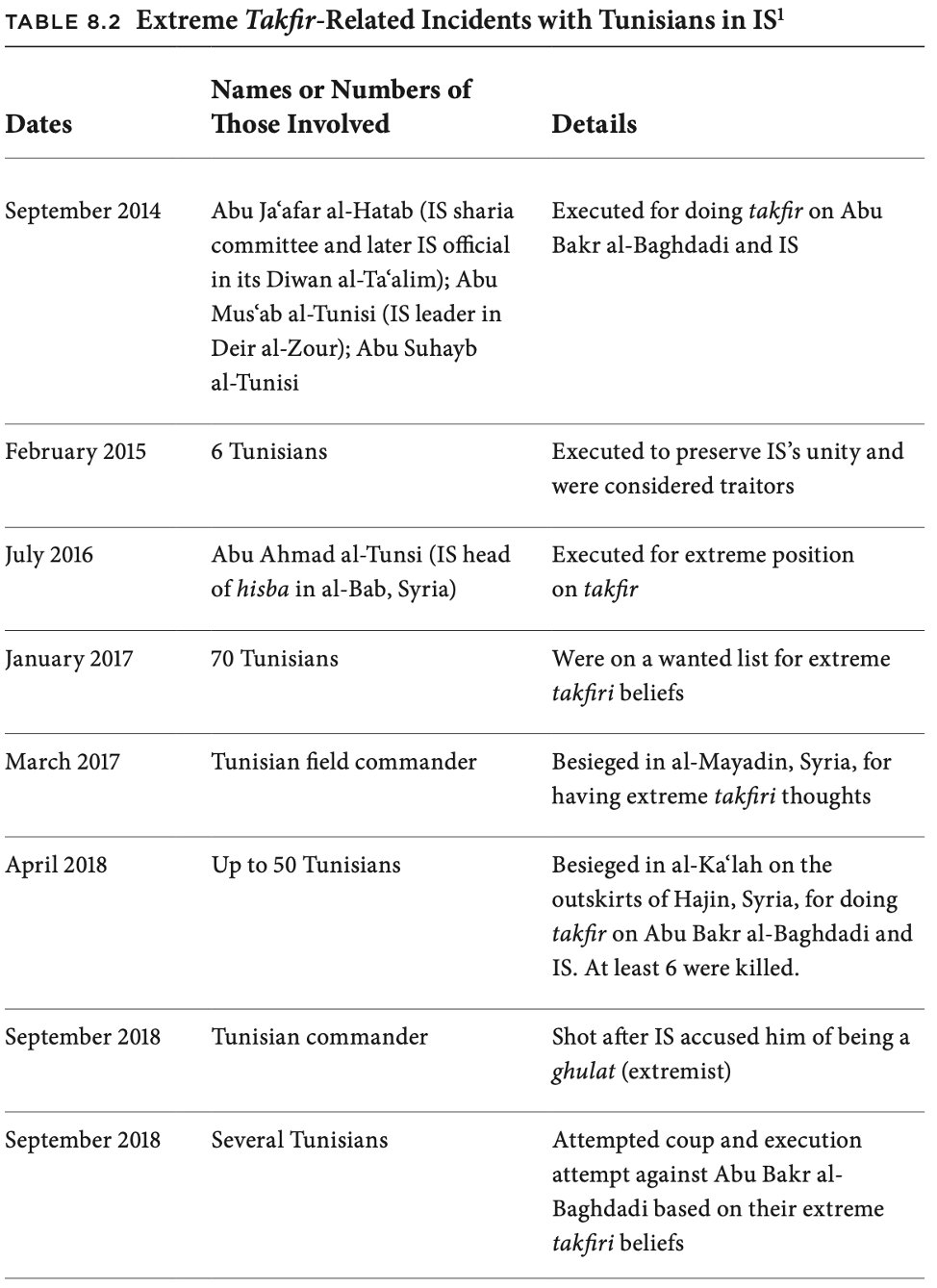

Shortly after providing more space to Tunisians due to their loyalty, their extreme positions on takfir came to light and increasingly became a problem for ISIS later in the year. In early March 2014 an audio leaked of a conversation between Abu Muhammad al-Tunisi, an ISIS sharia official in al-Hasakah, Syria; and Abu Mus‘ab al-Tunisi, an ISIS sharia official in Deir al-Zour; and Abu Usamah al-Iraqi, the wali (governor) of al-Hasakah, during which they described the Taliban and Usamah Bin Ladin as infidels.[25] A couple of weeks later another audio leaked of Abu Mus‘ab al-Tunisi, now doing takfir on AQIM [Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb] and AST and claiming that only ISIS is part of al-ta‘ifah al-mansurah (the victorious sect).[26] He also believes that “jihad will die” in Tunisia because of those two groups.[27] It should be noted that Tunisians were not the only ones associated with the Hazimi trend; in addition to al-Hatab, one of the early leaders in this trend was Abu ‘Umar al-Kuwaiti.[28] In August 2017, an IS scholar named Abu ‘Abd al-Malik al-Shami also highlighted that Egyptians, Saudis, Azerbaijanis, and Turks were among the early adopters of the Hazimi trend, along with Tunisians.[29] The increasing voice and strength of this trend, however, led to a backlash by some within the senior leadership of IS, who were worried about this excessive extremism in the use of takfir. This led to a series of arrests and then executions in August and September 2014, including of al-Hatab, Abu Mus‘ab al-Tunisi, and Abu Suhayb al-Tunisi.[30] In the following years there were a number of other public incidents related to the Hazimi trend (see table 8.2) that Tunisians were involved in as well.

Likewise, behind the scenes, those who were against the Hazimi trend within IS wrote several letters and memos that have since been leaked online that included details on later manifestations of this trend, which also highlighted some more Tunisians among a broader grouping of people. Some of them had positions within IS, including Abu Hudhayfah al-Tunisi, a member of IS’s Diwan al-I’alam (Administration of Media) and previously a judge of “real estate” in Wilayat al-Raqqah, and Abu Dhar al-Tunisi, the founder of IS’s Military Academy, which had lectures on warfare and tactics.[31] Beyond these two individuals mentioned for their extremism in use of takfir, IS’s Diwan al-Amn al-Am (Administration of General Security) notes some secret groups that came into being following the death of al-Hatab and his associates, including the Abu ‘Abd Allah al-Tunisi group and the Abu Ayub al-Tunisi group.[32] The latter group had the support of the wali (governor) of Aleppo, making it difficult to go after them even if the diwan viewed them as dangerous. Therefore, even if the Hazimi trend is less open publicly within IS, there remains some remnants of it left as of the fall of 2019.

Notes

[1] Haïfa Mzalouat and Malek Khadhraoui, “Fayçal, du jihad en Syrie à la désillusion,” Inkyfada, August 31, 2018; Lina Sinjab, “al-Qaeda’s Brutal Tactics in Syria Force Out Moderates,” BBC News, November 27, 2013; Mansour Omari, “Two Years an ISIS Slave,” Daily Beast, December 22, 2015; Yaroslav Trofimov, “In Islamic State Stronghold of Raqqa, Foreign Fighters Dominate,” Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2015; and Charlie Savage, “As ISIS Fighters Fill Prisons in Syria, Their Home Nations Look Away,” New York Times, July 18, 2018.

[2] “Birnamij hamuna 4—al-halaqah al-sadisah—tujarib shabab mugharar bi-him,” Saudi Channel 1, YouTube, March 5, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQ8SS1HmT2o.

[3] Abu Lababah al-Tunisi, “Series About the Causes of the Spread of Extremism in the Tunisian Youth: Why Are Tunisia’s Youth the Most Extreme in the Ranks of the State Organization?, Parts 2, 3, 4,” September 3, 2015, https://jihadology.net/2015/09/03/new-article-from-abu-lababah-al-tunisi-series-about-the-causes-of-the-spread-of-extremism-in-the-tunisian-youth-why-are-tunisias-youth-the-most-extreme-in-the-ranks-of-the-state-or/; and al-Maqalaat, “Tunisia: A Reason For the Current Extremism in the Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2015, copy retained in author’s archives.

[4] Abu al-Zubayr al-Qabsi, “al-Dawrah al-’ilmiyah al-ula li-l-shaykh ahmad bin ‘umar al-hazimi bi-tunis,” Ahl al-Hadith Forum, October 25, 2011; and “Dawrah ‘ilmiyah: Shaykh ahmad bin ‘umar al-hazimi,” Mawqah al-Islam fi Tunis, October 29, 2011, https://islamentunisie.com/?p=453.

[5] See https://masejed.weebly.com/index.html.

[6] Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia’s Clerical Establishment Database, created by Aaron Y. Zelin, available at http://tunisianjihadism.com, last updated August 10, 2016.

[7] Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia, “Khutbah of Abu Muhanad al-Tunisi,” al-Bayyariq Media, February 17, 2012.

[8] Salwa al-Tarhuni, “Bitaqah ida’a bi-sijin fi haqq ra’yis jami’ah al-khayr al-islamiyah bi- tuhamah tamwil al-irhab,” Tunisien, May 14, 2014, available at http://www.tunisien.tn.

[9] “Bayan bi-khasus iftitah ma’had ibn abu zayd al-qayrawani li-l-’ulum al-shari’ah,” March 1, 2012, http://majles.alukah.net/t97703.

[10] “Tariqah al-tasjil fi ma’had ibn zayd al-qayrawani li-l-’ulum al-shari’ah,” March 1, 2012, http://majles.alukah.net/t97703.

[11] Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia Facebook page, December 22, 2012.

[12] Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia Facebook page, January 15, 2013.

[13] As linked to by AST on its official Facebook page: Fiqh al-Muyasar fi Dhu’ al-Kitab wa-l-Sunnah, Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Islamic Affairs, Dawah and Guidance, 2004, https://ia800204.us.archive.org/10/items/fikh_moyasar1/fikh_moyasar1.pdf.

[14] Cole Bunzel, “Ideological Infighting in the Islamic State,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 1 (February 2019): 13–22.

[15] Tunisi, “Series About the Causes of the Spread of Extremism; and al-Maqalaat, “Tuni- sia: A Reason For the Current Extremism in the Jihadi Movement.”

[16] Abu Ja’afar al-Hatab, “Stance Ahead of the Third Annual Conference,” al-Bayyariq Media, May 13, 2013.

[17] Rania Abouzeid, No Turning Back: Life, Loss, and Hope in Wartime Syria (New York: Norton, 2018), 515–17.

[18] Bunzel, “Ideological Infighting in the Islamic State.”

[19] WikiBaghdady, December 14, 2013–June 13, 2014, originally posted here: https://twitter .com/wikibaghdady, and archived here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1wEQ 0FKosa1LcUB3tofeub1UxaT5A-suROyDExgV9nUY.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Islamic State, “Report on the Phenomenon of Extremism in the Islamic State,” November 14, 2015, https://jihadica.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/zahirat-al-ghuluww.pdf.

[25] “Shari’iyun da’ish yukafirun harakat taliban wa usamah bin ladin khatir jidan,” YouTube, June 28, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_LANfh2BOU.

[26] “al-Dawlah al-islamiyah ‘da’ish’ wa ‘aqidat al-takfir—da’ish tadu’i anaha al-ta’ifah al- mansurah wa ansar al-shari’ah ‘ala khata,’ ” March 13, 2014, originally available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvHnfeaBQ9E, author maintains a copy in his archives.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Tore Hamming, “The Extremist Wing of the Islamic State,” Jihadica, June 9, 2016, https://jihadica.dreamhosters.com/the-extremist-wing-of-the-islamic-state.

[29] Abu ‘Abd al-Malik al-Shami, “Sighs from the Islamic State Buried Alive,” August 2017, copy retained in the author’s archives.

[30] Islamic State, “Report on the Phenomenon of Extremism in the Islamic State.”

[31] “Message of the ‘Council of ‘Ilm’ on the State of the Extremists in the Media Diwan,” al-Turath al-‘Ilmi Foundation, 2018; and Abu ‘Abd al-Malik al-Shami, “Sighs from the Islamic State Buried Alive.”

[32] The Islamic State, “Report on the Phenomenon of Extremism in the Islamic State.” Other members of the Abu Ayub group included Abu al-Darda’ al-Tunisi, Abu al- Yaman al-Tunisi, Abu Qatadah al-Tunisi, Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Libi, Abu Khalid al-Tunisi, Abu al-Mu’tasim al-Tunisi, and Jahabdhah al-Tunisi.

Excerpted from Your Sons are at Your Service (c) 2020 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.