Nico Prucha

May 15, 2014

Following the recent airstrikes carried out against a convoy targeting al-Qaeda fighters in remote training camps in southern Yemen, Ali Fisher and Nico Prucha examine how the tales of drone strikes and civilian suffering claimed to be the result have become a frequent narrative for jihadi statements, videos and on forums. Analyzing the way word of the strikes and announcements of the martyrs spread via Twitter we find that jihadist groups are using the impact of drone strikes to strengthen the cohesion of remaining fighters, celebrate the martyrs, and attempt to derive sympathy from a wider audience.

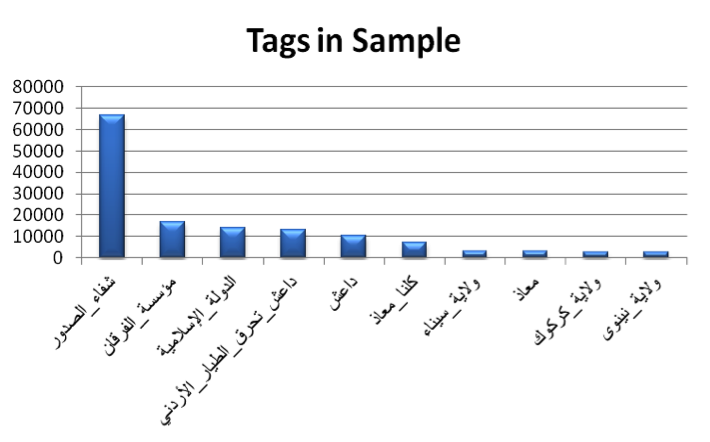

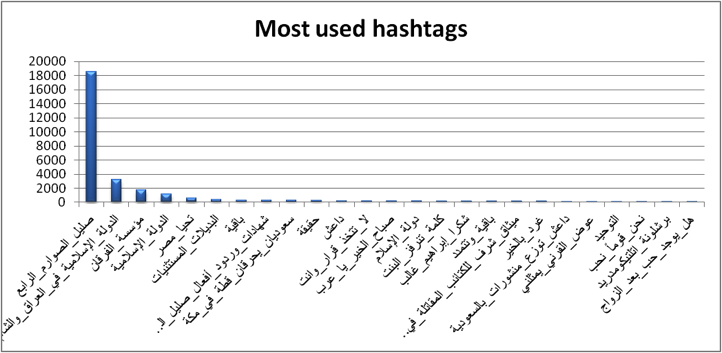

While the conversation, denoted by the Arabic hash tag for “martyrs of the American strike in Yemen” #شهداء_القصف_الأمريكي_باليمن)) was short-lived and quickly reached its peak when the majority of the martyrs had been announced. However, we also find that while a division between pro-ISIS and pro-AQ users can be identified, there is a shared positive opinion on AQAP and drone strikes in general, independent of the leaning of individual accounts towards ISIS or AQ Central.

Independent of the hash tag, AQAP’s media department issued two responses to the drone strikes end of April. The first response is a direct reply to the statements made by the Yemeni President Hadi, the other one is a commentary of AQAP commander Hamza al-Zinjibari; both documents were quickly translated into English and dispatched via Twitter and the ‘old media’ jihadi forums (here, here).

The Impact of Drone Strikes on Physical Networks – Limiting Online Jihadism?

The deaths of high ranking ideologues and leaders by missiles fired from unmanned aerial vehicles, that have in the past years become the operational backbone of the “war on terror”, have risen and seem to be the operational weapon of choice by military planners. With ideologues and media-valued activists such as U.S. citizens Anwar al-Awlaqi and his media operator Samir Khan killed in Yemen in 2011, or the targeted killing of the Libyans ‘Attiyatullah and Abu Yahya in 2012 in Pakistan only highlight prominent drone operations recently. Nevertheless, the extrajudicial killing of al-Awlaqi and Khan did not kill off the English jihadi magazine Inspire that had published a new edition in May 2012 under the title “winning on the ground.” This ninth edition (Winter 1433 / 2012) addressed its readers on the cover page, asking

“does the assassination of senior jihadi figures have any significance in validating Obama’s claims? After a decade of ferocious war, who is more entitled to security?”

It may be asserted that the U.S. operated drone program has similar affects on local populations as in Pakistan, although the degree differs from country to country. According to The Long War Journal, 354 drone strikes had taken place inside Pakistan and 95 bombing runs in Yemen. The impact of frequent or more regularly occurring drone strikes on the people on the ground is devastating and generates new grievances with innocents being either mistaken for legitimate targets or are nevertheless considered as acceptable collateral damage. A study on the impact of drone strikes in Pakistan is available here. The long-term side affects of drone warfare are open for debate, however, the tales of drone strikes and civilian suffering as a result of missile strikes have become a frequent narrative for jihadi videos and forums and are also addressed by scholars and journalists alike.

Killed civilians, mainly children, are pictured in jihadist propaganda material with the vow for revenge. The Shumukh al-Islam Forum in early May 2014 responded to the continuing drone activity inside Yemen that had recently killed a number of AQAP operatives. The administration of the forum via its media “workshop” (warsha) issued a forum thread showing several propaganda pictures and a video showing scores of killed people allegedly the result of drone strikes in Yemen. The “official account of warsha shumukh al-Islam for incitement” of the Shumukh al-Islam forum on Twitter is @warshshomokh1, which promoted both pictures and the video. The pictures in the forum thread relate the death of children to calls for revenge on a wider scale; other pictures visualized the close relationship of the U.S. and Yemeni government, in extremist reasoning defined as ‘one’ enemy, committed to the “war on Islam” likewise.

Drone Strikes in Yemen and the Response on Twitter

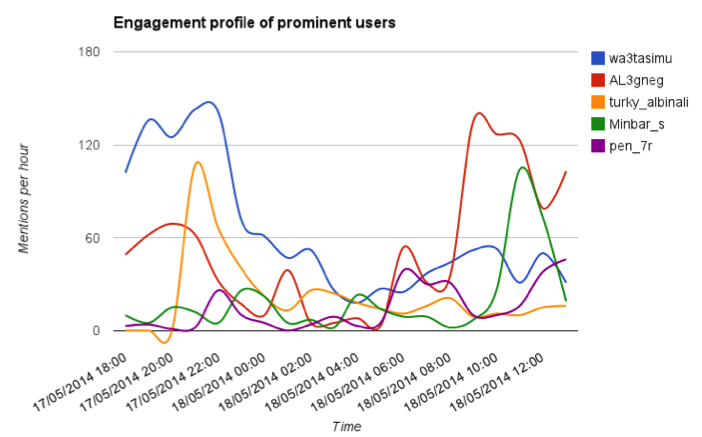

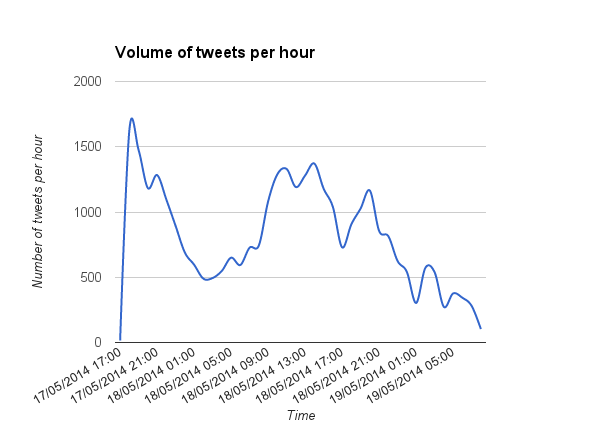

The posting of SSI in early May was the direct response to a drone strike that had killed about 40 AQAP members on April 21, 2014, as the New York Times reports. Shortly afterwards, on April 24, 2014, jihadi-linked accounts on Twitter started posting pictures and names of the alleged slain AQAP fighters. By using the hash tag #شهداء_القصف_الأمريكي_باليمن

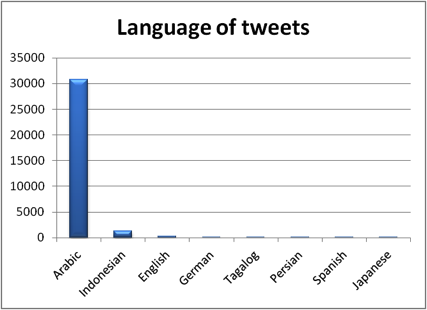

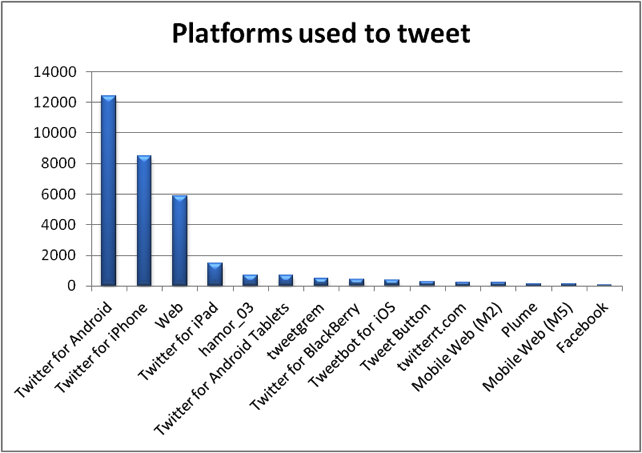

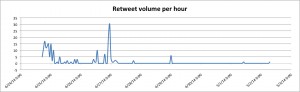

All in all about 200 Tweets were issued from April 24 to April 27; all Tweets are in Arabic. The hash tag translated to “the martyrs of the American strike on Yemen.”

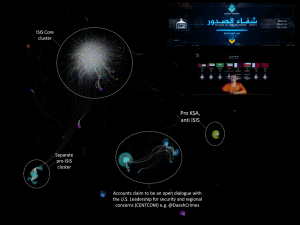

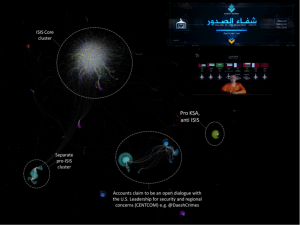

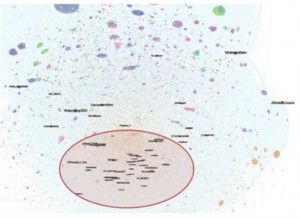

The distinctive feature of this Twitter network analysis is set on two key findings:

- a division between pro-ISIS and pro-AQ can be identified. The main underlining finding, however, is the common relation to the U.S. drone strikes in Yemen against AQAP, whereas most pro-ISIS media activists and followers nevertheless have high, if not higher, sympathies for AQAP. There is a shared opinion on AQAP and drone strikes, independent of the leaning of individual accounts towards ISIS or AQ Central.

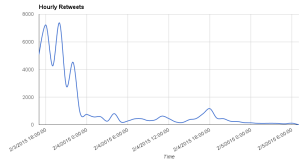

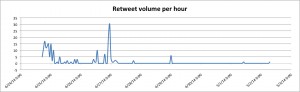

- The hash tag referring to the drone strike was short-lived and quickly reached its peak when the majority of the martyrs had been announced on Twitter.

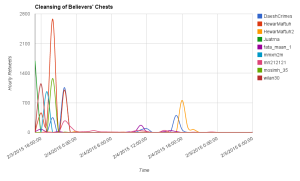

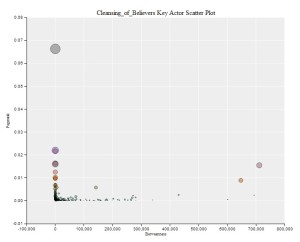

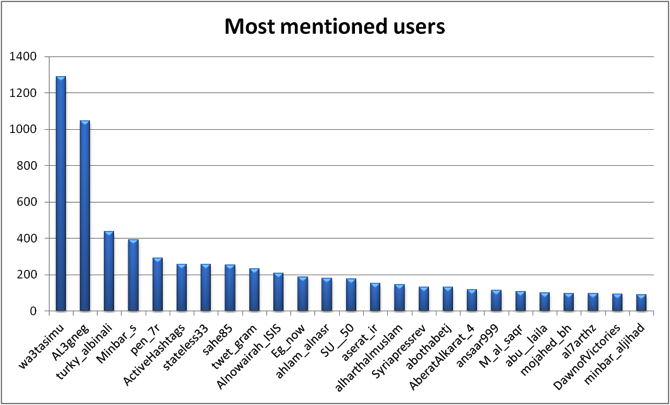

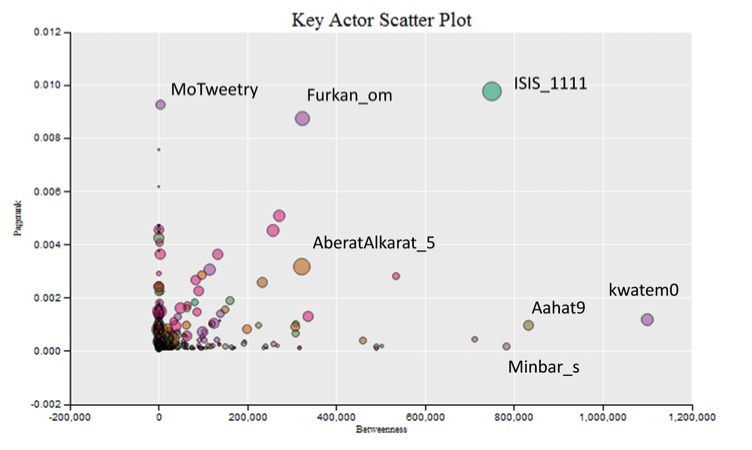

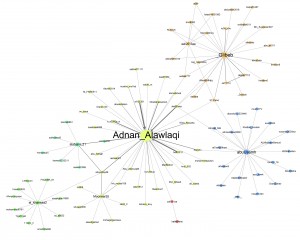

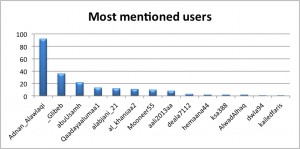

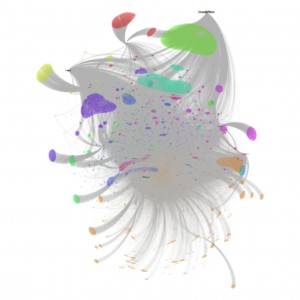

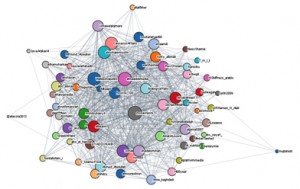

Four major hubs can be identified within this network on Twitter, with the respective accounts @_Glibeb, @AbuUsamh, @Adnan_Alawlaqi, and @al_khansaa2 as the most influential. These four major nodes are connected to each other by shared followers, who (re-) tweeted using the hash tag and by addressing accounts directly. Some of the interlinking accounts are further analyzed below.

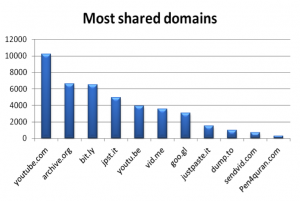

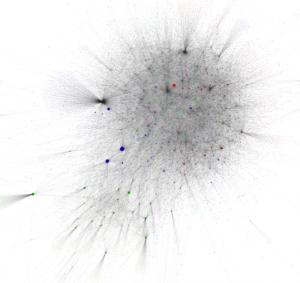

Networking about 200 Tweets relating to the U.S. drone strike in Yemen the fatter the arrow the more often the source mentions the addressed account (click to enlarge and zoom in)

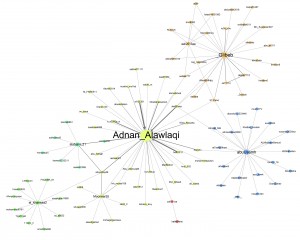

The biggest node in this network analysis is @Adnan_Alawlaqi, some of his followers are connected to the other three major nodes. By choosing “Alawlaqi”, the account claims a direct relationship to the Yemeni tribe and to the U.S.-Yemeni cleric Anwar al-Awlaqi who had been killed in a drone strike in 2011. For the avatar of this account Osma bin Laden has been chosen, the background picture shows “the martyr: Abu ‘l-Ghayth al-Shabwani”, a Yemeni AQAP fighter killed in a drone strike. For his web interface Twitter account, he has chosen the cover of the book “Why I Chose al-Qa’ida” which has been written by Abu Mus’ab, an AQAP affiliate who claimed being a member of al-Awlaq tribe. According to the book, Abu Mus’ab al-Awlaqi “was martyred in an American strike on Wadi Rafd in the Shabwa Province” in 2009. His full name is given as Muhammad ‘Umayr al-Kalawi al-‘Awlaqi. The foreword of the book has been written by AQAP chief Abu Basir (Nasir al-Wuhayshi), which evidently was finished shortly before the death of Abu Mus’ab. The about 80-page long book outlines in simple words and reasoning the motivation to have joined al-Qa’ida and serves as a guide to inspire and indoctrinate a non-Arabic audience. The English-language magazine Inspire has a regular section entitled “Why did I Choose Al Qaeda” where selected parts of the book are made available in English.

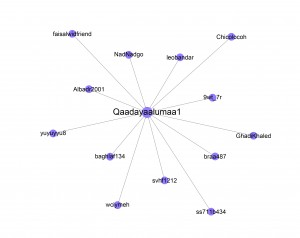

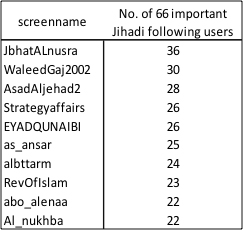

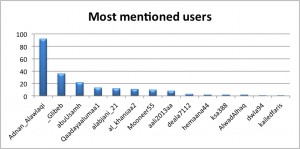

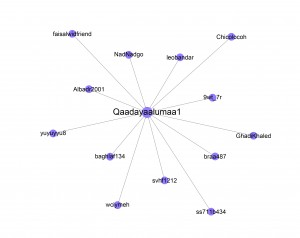

The most mentioned users in this data-set highlights the impact and importance of the major nodes, with @Adnan_Alawlaqi ranging at the top. @Qaadayaalumaa1 has been omitted in this analysis, although rank 4, it is not connected to the above network analysis. Instead, it is an independent sub-network that uses the same hash tag and shares similar content.

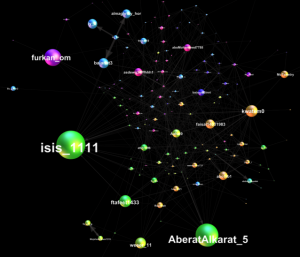

A not connected network sharing same content on Twitter

@Adnan_Alawlaqi has a little over 4,000 followers and issued more than 2,000 Tweets as of May 12, 2014. The account is primarily affiliated with “the organization of al-Qa’ida on the Arab Peninsula” and pictures from within Yemen and of drones are frequently published. It seems to be following the strict AQ conduct and has little to none connection to any ISIS related material.

Another major node in the network is @abuUsamh, as seen on the bottom right. According to his online profile, this is the account of Abu Usama al-Abini. His profile further states his clear favor of ISIS, hoping that

“the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham will remain and expand, by the will of God, #the lion cubs of jihad (#شبل_الجهاد) // my backup account is @abuusamh1.”

He refers to the “soldiers of Yemen” (jund al-Yemen) and lists his YouTube channel “greebe1.” His focus is also set on Yemen, but he approves and idealizes ISIS and their war in Syria as the future and considers them as an avant-garde that will soon arrive in Yemen as well. He has about 2,300 followers and issued 1,300 Tweets as of May 12, 2014.

@abuUsamh posted pictures of alleged victims of the April drone strike and provides further information. The name of the deceased seen here is given as “the Mujahid: Abu Tamim al-Qayfi (…) killed in the despicable American [missile] strike. Look at his smile!”

@abuUsamh is connected to @Adnan_Alawlaqi by three accounts, two of which also interlink to @_Glibeb. @Jeefsharp and @911Fahd interlink these two major nodes.

@_Glibeb refers to Jilbib al-Sharruri and has about 2,500 followers and issued close to 9,000 Tweets as of May 12, 2014. He too has a greater leaning towards ISIS and re-tweets and disseminates videos published by ISIS’s media channel al-Furqan:

“Special report on the civil service work by the Islamic State in Aleppo before ISIS was betrayed; preparing: Flour and bread – health care – electricity – overall services.” Two links are set in the Tweet, the first leads to YouTube where a sequence of the video Services provided for by the State of the ISIS series Rasa’il min ard al-malahem, part 14, is shown. The second link extends the civil aspect of ISIS by directing to a Facebook group.

Like most other Twitter accounts linked to this hash tag, @_Glibeb posts pictures of male victims of the airstrike with the impression that they indeed had been AQAP members. He may be of Yemini origin and possibly related to some of the deceased by tribal relations. The name “al-Sharruri” pops up frequently in Yemen and has also come to use among ISIS members in Syria. Abu Jandal al-Sharruri appeared in a video a while ago and the picture used to commemorate him on Twitter is a screen grab thereof.

The fourth most important node in this mini-network of approximately 200 Tweets is an account the reader of our work may already be acquainted with: @al_khansaa2. This account in this network is only linked via the account @aboyahay88 to the main node of @Adnan_Alawlaqi. The main objective, as for the others, is to document the martyrs of the drone strike and provide affirmative comments on pictures of killed AQAP members. All pictures issued within this particular hash tag are male, some are flashing weapons, and others are a screen grab from a jihadi video. One of the pictures shared by @al_khansaa2 is a typical Yemeni dressed man flashing his janbiyya a specific type of dagger with a short curved blade that is worn on a belt. This is a sign of male hood and pride and very common on the streets in Yemen.

@aboyahay88, the account linking @al_khansaa2 to @Adnan_Alawlaqi also connects to two other nodes, @alabjani_21 and @Mooneer55. @aboyahay88, whose screen name is the sincere (الصديق) referring to Abu Bakr further states on his profile “We belong to God and to Him we shall return”, taken out of the Qur’an (2:156). This part of the Qur’an is often cited at funerals and generally expressed to sympathize with the deceased, emphasizing the conviction in the existence of the afterlife. Apart from this @aboyahay88 is a low-key and low profile node with only 438 followers and over 4,000 Tweets as of May 12, 2014. The majority of his shared pictures are Yemen related with some pictures apparently taken by a cell-phone, perhaps implying he has taken these himself. Other pictures are from ISIS accounts on Twitter. His Twitter account is linked to the open Facebook group al-Ta’ifa al-Mansura that has eleven members but no actions or shared material whatsoever. All eleven members are part of the jihadist cluster network and show related iconography.

@alabjani_21 is one of the more prolific Twitter accounts in this network, although not the biggest node in this particular network analysis. He has over 9,000 followers and Tweeted close to 17,000 times as of May 12, 2014. The chosen avatar is Ayman al-Zawahiri with both of hands held up towards the viewer – in a praying fashion, although it is clearly a screenshot of one of al-Zawahiri’s sermons televised by as-Sahab. @Mooneer55 in turn only has 787 followers but Tweet an impressive 11,700 times as of May 12, 2014. This account clearly aligns itself to ISIS with an avatar showing Abu ‘Umar al-Baghdadi and referencing “the book leading the right way” (kitab yahdi) and the “sword that assists” (sayyf yansur), as detailed in the chapter The ‘Arab Spring’ as a Renaissance for AQ Affiliates in a Historical Perspective.

Of greater interest are the two accounts linking the three nodes of @Adnan_Alawlaqi, @_Glibeb, @abuUsamh, which are:

@JeefSharp: This account is also in clear association to ISIS, stating in his profile,

“I pledge allegiance to the amir al-mu’mineen Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.”

He has a meager 185 followers and around 3,500 Tweets. The majority of these are retweets of ISIS related accounts and material, that is in parts also anti-Muslim Brotherhood who demand action instead of passive protests.

And @911Fahd: This account showcases the killed leader of the TTP, Hakim Allah Mehsud with an ISIS related avatar. He has a little over 1,000 followers and Tweeted an incredible 66,454 times as of May 12, 2014. The majority of his shared pictures are related to Iraq and ISIS but also include a picture of the Gaza-based Jund Allah and their leader Abu al-Nur al-Maqdisis – all of whom had been wiped out by their rival HAMAS in 2008. Like the above account, @911Fahd mainly retweets and is interlinked to high profile users such as @al_khansaa2 or @Adnan_Alawlaqi.

Conclusion

The analysis of this mini-dataset has shown that jihadist groups are framing the impact of drone strikes to strengthen the remaining fighters, celebrate the martyrs, and attempt to derive sympathy from a wider audience.

Drone strikes are a unifying issue, while a division between pro-ISIS and pro-AQ users is visible in terms of who they interact with, we did not find the same division in the content of 200 tweets which used this specific hash tag. On this specific issue, jihadist opinion appears to have been independent from individual allegiance to or sympathy for AQ or ISIS. While some pro-ISIS users openly wish for the emergence the Islamic State as a part of ISIS in Yemen, the pro-AQ accounts stuck to what al-Zawahiri had called for, unity among the Mujahideen. Other users simply admired the martyrs and sought to document and share as widely as possible reports of this ‘crusader’ attack.

This mini-dataset from Twitter has focused on two specific drone strikes in April 2014 in Yemen, but it is just one part of a wider cluster of jihadist content that has been exploding in terms of quantity and quality, particularly in relation to the war in Syria. In this wider context, drone strikes have impacted jihadist activity and ideology. For example, with the reality of drone warfare hitting jihadist groups hard in recent years, jihadist videos and ideological writings have adopted the theme of spies among the Mujahideen. A number of videos have emerged showcasing the confessions and subsequent execution of alleged spies. In addition, Abu Yahya al-Libi commemorated his friend and comrade Abu ‘l-Layth al-Libi after he was killed in a drone strike in 2008 and subsequently published a detailed book on shari’a law policy for jihadist groups a year later. Ironically, Abu Yahya was killed himself in Pakistan in a drone strike in June 2012 but his work has become an integral handbook for jihadist implementation of shari’a law in dealing with indicted Muslim spies among the ranks of the Mujahideen. It is often referenced in videos showing the execution of alleged spies in Yemen and Somalia. Through the combined analysis of the written and audio-visual layers, the way alleged Muslim spies are framed for jihadist propaganda can be assessed and tied into events such as this case study – the topic of a future post on Jihadica.