Hamas and the Jihadis

The Palestinian terrorist group Hamas has long been a source of controversy in the world of Sunni jihadism. Especially since it participated in and won the elections of the Palestinian Legislative Council in 2006, going on to form a unity government with Fatah, the dominant faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the following year, the group has generally been shunned by jihadis. Hamas’s roots in the Muslim Brotherhood, its embrace of the “polytheistic” religion of democracy, its perceived failure to rule by Islamic law in Gaza, its unholy alliance with Shiite Iran—all of this has made it unpalatable, if not anathema, to the adherents of Jihadi Salafism (al-salafiyya al-jihadiyya). The question that divides jihadis is exactly what level of condemnation is called for. Is the right approach to pronounce takfir (excommunication) on Hamas, or on certain elements of it? Is Hamas to be supported when it faces off against the Jewish state? Are its war dead to be considered martyrs?

The recent hostilities between Hamas and Israel have brought the controversy over Hamas back to the fore, shedding new light on the jihadi movement’s ideological fault lines. The first division is that between al-Qaida and the Islamic State, and as one would expect it is the Islamic State that takes the harder line against Hamas. There is another fault line, however, that runs between two ideological camps on the pro-al-Qaida side of the jihadi movement. It is here, as will be seen, where the most intense debate has taken place. One of the camps has not shied away from criticizing al-Qaida itself.

Al-Qaida vs. the Islamic State

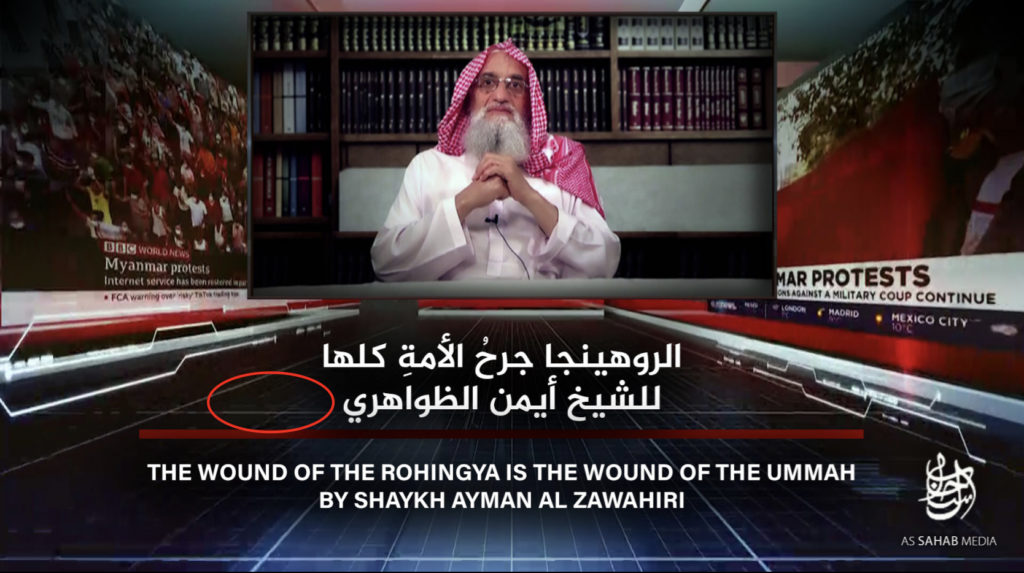

Shortly after the conflict between Israel and Hamas began on May 10, when Hamas fired more than 150 rockets into Israel and Israel responded with airstrikes, most jihadi groups, including the various branches of al-Qaida, issued statements of solidarity with the Palestinians. The statements also decried the perceived Israeli aggression on the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, where clashes had been taking place between worshippers and Israeli security forces since May 7. Al-Qaida central, through its al-Sahab media outlet, issued three such statements between mid-May and early June.

The first statement appeared on May 11 in the form of an issue of al-Qaida’s occasional newsletter, al-Nafir. Titled “Al-Aqsa in the Care of the Descendants of al-Bara’ ibn Malik,” it appears to have been written before the air war began as its focus is the Palestinian demonstrations around the al-Aqsa mosque. Al-Qaida here likens the fearlessness of the demonstrators to that of the Prophet’s companion al-Bara’ ibn Malik, who was launched into a walled area of thousands of apostates in the so-called “wars of apostasy” in early Islam. The issue also quoted at length from a March 2002 speech by Osama bin Ladin in which he inveighs against normalization with the Jewish state and encourages Muslims to kill Americans and Jews by any means possible.

Several days later, on May 17, came a more controversial statement from al-Qaida’s “general leadership,” titled “Statement of Love, Honor, and Support for Our People in Palestine.” The purpose of the statement was to salute the “mujahidin” in Gaza and their launching of “jihadi missiles toward the Zionists.” The statement never mentions Hamas, but it does mourn the death of one of its military commanders. Toward the end, the al-Qaida leadership offers its condolences (or congratulations) to the Palestinians on “your pious martyrs, foremost among them the heroic leader Basim ‘Isa Abu ‘Imad.” Basim ‘Isa, who was killed in an Israeli airstrike in Gaza on May 12, was a top military commander of the al-Qassam Brigades, Hamas’s armed wing. As noted by the analyst Wassim Nasr on Twitter, the praise for Basim ‘Isa here was in keeping with a preexisting al-Qaida policy to distinguish between the political and military wings of Hamas. That policy was elucidated over a decade ago by the al-Qaida commander Mustafa Abu al-Yazid (d. 2010) after he made the mistake of saying in an interview that “we and Hamas share the same thinking and the same methodology.” Following criticism of his remark, Abu al-Yazid issued a clarification acknowledging that he had misspoken and explaining that the approach of the al-Qaida leadership is to distinguish between Hamas as a political organization, which had committed terrible methodological errors such as embracing democracy, and the righteous mujahideen fighting under Hamas’s banner (i.e., the al-Qassam Brigades, or at least some of them).

The third al-Qaida statement appeared on June 2, two weeks after a ceasefire was reached between the warring parties on May 21. Once again taking the form of an issue of al-Qaida’s al-Nafir newsletter, the statement hailed Hamas’s “sword of Jerusalem” campaign as a great victory that should be seized on “to revive the duty of jihad” in the youth of the Muslim umma. The model of initiating battles to defend mosques under siege from unbelievers and apostates was one to be followed across the Islamic world. The statement went on to praise “the mujahidin in Gaza” and in particular “their heroic leader Muhammad al-Dayf,” the supreme military commander of the al-Qassam Brigades. The singling out of al-Dayf further exemplified the al-Qaida leadership’s fondness for Hamas’s military wing to the exclusion of its political wing.

Taken together, the three statements show al-Qaida posturing as the ally of the al-Qassam Brigades and trying to portray the hostilities with the Jewish state as part of al-Qaida’s larger war with the Americans, the Zionists, and the “client” Arab regimes. Nowhere in these statements is there any hint of criticism of Hamas as a political organization, unless that is to be read in the omission of Hamas’s name. In the past al-Qaida has issued harsh condemnations of the Hamas political leadership, but here no such thing is to be found.

The Islamic State could not have responded more differently to the war between Hamas and Israel. After more than a week of silence on the matter, the official line came in the editorial of the May 20 issue of the Islamic State’s weekly newsletter, al-Naba’. Titled “The Road to Jerusalem,” the editorial condemned Hamas (never mentioned by name) as a proxy of Shiite Iran and as part of its axis of “resistance.” Hamas’s warfare was not to be considered jihad as it served the interests of the Iranians and their plot for regional domination. “The difference between jihad and resistance is as the difference between truth and falsehood,” the editorial read. “Whoso allies with those who curse the Prophet’s wives [i.e., the Shia] will never liberate Jerusalem … and whoso differentiates between the Rejectionists [i.e., the Shia] and the Jews will never liberate Jerusalem … Indeed, we consider the mujahid who lies in wait for the Rejectionists in Iraq to be closer to Jerusalem than those who show loyalty to the Rejectionists and burnish their image.” The editorial went on to claim that all of the Islamic State’s battles “east and west are in fact steps in the direction of Jerusalem, Mecca, al-Andalus, Baghdad, Damascus, and all other captured Muslim lands.” In other words, it is the Islamic State, and not Hamas, that holds the promise of liberating Jerusalem.

Perhaps the most notable line in the editorial was a remark toward the end rejecting the idea of Palestinian exceptionalism. “The soldiers of the caliphate,” it stated, “have not exaggerated the issue of Palestine and have not made it an exception among the issues of the Muslims … They have not differentiated between the blood of their Muslim brethren in Palestine and the blood of their brethren in other lands.” This is a remarkable statement, and one that illustrates a stark difference between the Islamic State and al-Qaida regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Unlike al-Qaida, the Islamic State is not interested in posing as the ally of whatever Sunni Muslim group is waging war against the Jewish state. For the Islamic State, any group that deviates from its methodology (manhaj) is simply not worthy of honor and support.

On June 21, the Islamic State’s official spokesman, Abu Hamza al-Qurashi, delivered an audio address that echoed much of the sentiment of the editorial. Al-Qurashi ridiculed the idea that Hamas could ever bring victory to Palestine and urged the Palestinians not to be deceived by the rockets launched by Hamas “in service of their Iranian masters.” Hamas was hypocritical for condemning the Gulf states’ normalization with Israel when it had normalized relations with “Zoroastrian, Safavid Iran.” As in the editorial, the idea here is that it is folly to differentiate between the Jews and the Shia.

Al-Maqdisi vs. Abu Qatada

Among jihadis opposed to the Islamic State and generally aligned with al-Qaida, a divide has emerged in recent years between two competing ideological camps—namely, those who side with the more hardline ideologue Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, and those who ally with the relatively more moderate Abu Qatada al-Filastini. Both men, who are Palestinian-Jordanians, have active social media presences and devoted followings. Much of their disagreement has revolved around the issue of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Syria, which al-Maqdisi has condemned and Abu Qatada praised. The matter of Hamas has proven equally controversial.

The war of words over Hamas, which played out on the messaging app Telegram, began on May 13 when al-Maqdisi responded to a comment by the jihadi scholar Na’il ibn Ghazi Musran, who is aligned with Abu Qatada. Musran had written that Gaza was “the standard of distinction between faith and unbelief, and the line separating monotheism (tawhid) in its entirety from apostasy in its entirety.” The author was referring to the different reactions in the Arab world to the Gaza conflict, his point being that those unsupportive of the Palestinian belligerents were in “the camp of apostasy” and those supportive were in “the camp of truth.” In his response, al-Maqdisi ridiculed the idea that “Gaza is the standard,” as the ongoing battle was not one between tawhid and unbelief. He cited what he saw as the outright apostasy of some Palestinian youth and their adherence to pagan nationalism. Addressing the people of Palestine, he wrote: “Do not expect victory from God so long as you are silent about the reviling and cursing of God around you.”

Later that day, Abu Qatada authored a brief response in which he objected to such casual dismissal of unspecified Palestinian youth as apostates. “It is incumbent upon us,” he wrote, “to treat the Muslim youth, even if they are people of sin, as belonging to us. We should understand them as belonging to us and being of us, for the call to expel them from the umma means making them the soldiers of Satan, and making them against us and against Islam. This is a profound error.” Abu Qatada did not believe that Hamas’s efforts would achieve “complete victory and the elimination of the Jewish state,” but nonetheless “these winds of faith in Palestine,” he said, referring to Hamas’s military operations, keep “the spirit of jihad” alive and renew faith in “the necessity of waging jihad against the unbelievers and the apostates.” And likewise, “they teach us to keep in check our quarrels with the Muslim sinner, the Muslim innovator, and the Muslim who errs.”

If Abu Qatada’s view was that the Gaza conflict ought to teach jihadis to be more tolerant and openminded, al-Maqdisi’s view was the opposite. In a post published on May 14, al-Maqdisi accused a certain unnamed shaykh (ba‘d al-shuyukh) of “exploiting these events to spread error and confusion.” “What is necessary,” he retorted, “is that these occasions and battles and wars be exploited to teach people their tawhid and their true religion, not to dilute it, change it, and distort it with false conceptions.” The problem with “making Gaza and Palestine the measure of unbelief and faith,” he reiterated, was that it overlooked the transgressions of the those purporting to wage jihad. “It is impossible for victory to come,” he declared, “from the exaltation of the Rejectionists of Iran and its affiliated parties that attack the honor of the Prophet’s wives, pronounce takfir on the Companions, and kill the Sunnis in Iraq and al-Sham.” In a subsequent post published the next day, al-Maqdisi clarified that while he supports the military efforts of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad against the Jews, he nonetheless does not consider them “jihad in the path of God”; for the path of these groups is not “tawhid and dissociation from all forms of polytheism and idolatry,” but rather “exalting and burnishing of the image of Rejectionist Iran.”

Al-Maqdisi vs. al-Qaida (and Abu Qatada)

The war of words between al-Maqdisi and Abu Qatada went on hiatus for about two weeks. It resumed on June 1 when al-Maqdisi authored a post condemning al-Qaida’s statement mourning the death of the Hamas military commander Basim ‘Isa. In the post, titled “Questions Posed to the Brothers at al-Sahab,” al-Maqdisi presented his criticism in the form of questionings attributed to others. “Many mujahid brothers, shaykhs, and preachers were displeased,” he wrote, “by the al-Sahab statement’s exaltation of the al-Qassam leader who was killed in the recent war in Gaza, and they wondered astonishedly: ‘Are our brothers not aware of the deviation of Hamas and its leadership from the path of tawhid in favor of the path of democracy, and their alignment with Hizb al-Lat [i.e., Hizbullah] and Bashar [al-Asad] and Iran?’” Al-Maqdisi continued in this way, referring to the “surprises, shocks, and perturbations” that have succeeded one after the other since the mourning of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi by some of the al-Qaida leadership. “Has the methodology (manhaj) changed?” he asked. “Or have the ranks of al-Qaida been penetrated by those who pay no heed to the purity of the manhaj? … It is presumed that al-Qaida continues to condemn the advocates of democratic Islamism and to dissociate from their manhaj, so how can it mourn their dead when they died on behalf of democracy? And how can it exalt their military leaders who in turn exalt Iran and Bashar and choose the path of democracy?” Al-Maqdisi was putting it out there that a lot of supporters of al-Qaida, himself included, were aghast at such praise for Hamas, even if the praise was restricted to Hamas’s military wing.

The following day, Abu Qatada responded to al-Maqdisi with a brief post implicitly rebuking him for suggesting that Hamas’s war dead were not martyrs (al-Maqdisi had pondered how al-Qaida could “mourn their dead when they died on behalf of democracy?”). Hamas was far from perfect, Abu Qatada explained, yet it nonetheless deserved praise for having “returned the Islamic identity” to the Palestinian cause that had been dominated by leftist and secularist parties. For this reason, he said, and because the secularist alternative is far worse, the critics of Hamas have generally been restrained in their criticism. The right way to deal with them, he declared, was to seek their improvement (ta‘dil) and not their destruction (tadmir). “Their dead are martyrs and their legal status is Islam,” he concluded. “Patience concerning their errors, together with the proffering of advice, is the right-guided sunni way.”

Al-Maqdisi’s response, which appeared the next day, was to insist that “whoso is killed in the path of democracy, and in support of a group that refrains from implementing the Sharia and chooses democracy, is not a martyr; rather he is a corpse (fatis), bother some though it will.” In the same post, al-Maqdisi launched into a comparison of Hamas and the Islamic State, both of which, as he explains, have killed their opponents and exposed their civilian populations to bombardment. Though al-Maqdisi has long been a critic of the Islamic State, here he suggests that the caliphate is superior to Hamas in that it has implemented the Sharia as opposed to democracy and does not show loyalty to idolatrous tyrants (tawaghit). Why then, he asks, addressing Abu Qatada (though not by name), is it your view that we must approach the Islamic State as something to be destroyed (tadmir) but Hamas as something to be improved (ta‘dil)? Al-Maqdisi’s point here was not that the Islamic State is improvable while Hamas is not. His point, rather, was that if the Islamic State is irredeemable then Hamas is doubly so, since Hamas is worse than the Islamic State in certain ways.

This time Abu Qatada did not respond. Al-Maqdisi would follow up to reaffirm that “whoso dies in the path of democracy is a corpse, not a martyr,” and later he would author a long post quoting some of Abu Qatada’s older works that were highly critical of Hamas and its ilk. The most recent post by Abu Qatada regarding Hamas was actually a statement condemning the group for allying with Iran and its Shiite proxies, and particularly the Houthis whom a Hamas representative had recently honored with a medal. Yet even here it was clear that Abu Qatada considered Hamas a Muslim group; the criticism was harsh but still intended as constructive.

Whither al-Maqdisi and al-Qaida?

As noted above, the jihadi reactions to last month’s Israel-Hamas war point to two fault lines in the Sunni jihadi movement: one between the Islamic State and al-Qaida, and one in the pro-al-Qaida side of the movement between the followers of al-Maqdisi and the followers of Abu Qatada. Al-Qaida, as I have written before, almost certainly would like to hold on to both ideological camps, but increasingly it is alienating al-Maqdisi and his followers. The change in approach appears to be by design. With the Islamic State representing the more extreme and intolerant version of Jihadi Salafism, al-Qaida is intent on presenting itself as the movement’s more moderate face. To that end, it has taken a softer line on mainstream Islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas and played down the emphasis on ideological exclusivism promoted by al-Maqdisi and his camp.

Al-Qaida has long wavered between a more pan-Islamist and a more Salafi (i.e., doctrinally exclusivist) tendency, and today the pan-Islamist tendency has the edge. Al-Maqdisi has taken note of this development, hence his questioning whether al-Qaida has “changed its methodology.” For the supporters of the Islamic State, the answer to this question is obvious and al-Maqdisi knows it. As one Islamic State supporter recently wrote, addressing al-Maqdisi, “Yes, it has changed, and you have ceased to have any value to them and they no longer pay any heed to what you say. Soon they may issue a statement in which, implicitly or explicitly, they dissociate from you and your extremism.” The writer was probably overstating the divergence between al-Maqdisi and al-Qaida; neither is eager for a divorce. But if al-Maqdisi continues to express outrage at what he see as the accumulating deviations of al-Qaida, then a breakup of sorts may well be inevitable.