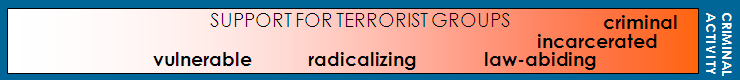

In my previous post, I proposed a minimal definition of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) as reducing the number of terrorist group supporters through non-coercive means. I also suggested that the spectrum of support ranges from those who are vulnerable to becoming supporters to those who are engaged in criminal activity.

There are pros and cons associated with intervening in each group. The three groups at the far right of the spectrum are the easiest to identify because they have either consistently voiced their support for a terrorist organization or taken action on its behalf. Although they are extremely difficult to dissuade, focusing on them risks less blow back from the broader communities of which they are a part. There is also less risk of straying into the policing of thought crimes.

Conversely, the two other groups, “vulnerable” and “radicalizing,” are theoretically easier to dissuade than the others but they are far, far harder to identify. Because they are harder to identify, focusing on them risks alienating the broader communities of which they are a part and can easily stray into the policing of thought crimes.

Countries will focus on different groups for non-coercive intervention depending on the nature of the terrorist threat they face and their perceptions of risk. In the United States, AQ supporters generate the most concern and the government’s CVE focus is on the vulnerable and radicalizing populations, whose size it hopes to shrink by building community resilience. U.S. government officials believe this approach is more holistic than law enforcement alone. By comparison, white hate groups generate far less concern and the CVE focus, if any, is on turning around their law-abiding and incarcerated supporters.

Based on the incredibly low numbers of AQ supporters in the United States (see Charlie Kurzman’s recent study), the United States should treat the problem of AQ support like it treats supporters of white hate groups. It should focus on turning around law-abiding and incarcerated supporters rather than reaching out to the broader communities of which they are a part. This approach may not suit law enforcement (which prefers to build cases), the administration (which wants to increase the resilience of US Muslims against al-Qaeda propaganda), civil libertarians (who worry about infringing on personal freedoms), or large swathes of the public (who are terrified of fifth columns). But it is commensurate with the threat; its success can be measured; it carries less risk of alienating communities from which terrorists arise; it undermines the narrative that these communities are potential threats; and it is far less threatening to civil liberties than the current approach.

All of that said, I am not sanguine about the possibility of turning around law-abiding or incarcerated supporters of terrorist groups. It is incredibly difficult, particularly given the intractable nature of larger political problems that drive some forms of terrorism. But if counter terrorism is to involve more than just locking people up, it should not stray too far from stopping bomb throwers into social engineering and thought policing. (As an experiment, read this excellent study of Zachary Chesser‘s radicalization and consider how the U.S. might have dealt with him differently.)

Recommending that the U.S. government should reorient its domestic CVE policy toward dissuading law-abiding and incarcerated AQ supporters does not mean that the government is the best suited to do it. Neither does it imply a certain way to go about it nor that this approach will work in every country. In my next (and final post), I’ll survey a range of CVE programs and explore who is best suited to carry them out and how effective they are.

Update: J.M. Berger kindly spiffed up and clarified my graphic.