Reading Kadyrov in al-Sham: ‘Adnan Hadid on Chechnya, Syria, and al-Qaida’s Strategic Failure

In his recent article for Jihadica, Aaron Zelin proposed the emergence of a tripolar jihadi world consisting of al-Qaeda (AQ), the Islamic State (IS), and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). While the first two poles are competing for the legitimacy and leadership of global jihadism, HTS has already departed the global arena and focused its efforts on running its proto-state in Idlib, Syria. Disputes between the three poles are intractable due to the ideological intransigence of IS and, to a lesser degree, of AQ, in addition to the political pragmatism of HTS, which has been conceived by the other poles as a deviation from the “right” path.

Understandably, a group like AQ, which perceives itself as the pioneer of jihadi Salafism, believes in its right to represent and lead the movement as was its role before the emergence of IS and HTS. This belief can be seen in the writings of AQ-aligned writers such as ‘Adnan Hadid, who periodically pens essays commenting on and analyzing global political events, assessing the status of jihadism, and theorizing a lucid political vision for jihadi groups to follow.

“‘Adnan Hadid” is almost certainly a nom de guerre, the two parts of his name appearing to be a tribute to ‘Adnan ‘Uqla and Marwan Hadid, two figures associated with the Fighting Vanguard of the armed branch of the Syrian Brotherhood.[1] Marwan Hadid was the group’s founder in the mid-1970s and among the first Islamist figures to espouse jihadi thinking and to fight against the Ba’ath regime in Syria.[2] ‘Adnan ‘Uqla was the leader of the Fighting Vanguard until his capture in 1982. Although ‘Adnan Hadid’s works have tackled global issues such as the 9/11 attacks and the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand in March 2019, and regional issues such as the Libyan conflict, his main focus has been on the Syrian conflict, or al-jihad al-Shami (“the jihad of the Levant”) as it is known by jihadis, which could suggest that he is a Syrian national.

The present article provides a thematic analysis of Hadid’s essay titled “Between Chechnya and al-Sham … Lessons and Examples: A Brief Political Study of the Chechen Experience and the Future of al-Sham,” which was published on the AQ-affiliated website Bayan in July 2020. The 102-page essay forms an extensive reflection on the failures of both the Chechen jihad experience of the 1990s and 2000s and the Syrian jihad that began in 2011. It is divided into an introduction and six “axes,” or chapters. The first four consist of historical explorations and political analyses of the pre-Chechen-wars phase, the first and second Chechen wars (1994-1996, 1999-2009), and the period between them. Chapter Five compares the rise of current Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov to that of HTS leader Abu Muhammad al-Jolani. The final chapter, titled “Back to al-Sham,” is dedicated to highlighting the “strategic mistakes” of Osama bin Laden and Aymen al-Zawahiri in the arena of Iraq and Syria.

The Chosen Trauma

Hadid begins his essay by assessing the state of the jihadi movement as it has developed since the 9/11 attacks. The salient feature of most jihadi battlefields nowadays, he says, is the repetition of errors and the failure to learn from them. “The [same] historical, structural, and organizational errors,” he writes, “are being repeated from battlefield to battlefield, producing the same putrid secretions whose bitterness the umma has tasted over and over again for years.” By bringing up events that led to the defeat of jihadi groups before and during the Chechen wars, and identifying similar errors in al-jihad al-Shami, Hadid constructs what has been called by Jan Hjärpe, a scholar of Islamic Studies, “the chosen trauma.”[3] This is “a catastrophe in the past, a historical disaster … that has the function of signifying ‘group belonging’ and to create a pattern of behaviour” intended, among other things, to prevent the reemergence of the “trauma.” In addition to othering those who do not belong to the group, the “trauma” has the effect of uniting the group’s members in the effort to prevent whatever might lead to its reoccurrence.

For Hadid, nothing is more traumatic than the “recurring defeats of Muslims” living in Russian zones of influence over the last three centuries, and particularly the defeat of the Chechen jihad fighters during the 1990s and 2000s. The aim of his essay is to examine the critical failures that led to defeat in the Chechen wars—failures that would reoccur in al-jihad al-Shami—in hopes of not repeating them in the future. Hadid’s presentation of the history of the Chechen wars is largely based on several books including Sebastian Smith’s Allah’s Mountains: Politics and War in the Russian Caucasus, Steven Lee Myers’s The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin, and Lilia Shevtsova’s Putin’s Russia, reflecting a considerable knowledge of the history of Chechnya and the Caucasus.

Reoccurences

Three years after the announcement of its independence from Russia in 1991, the new Chechen state, known as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, witnessed the first Chechen war, during which the Russian army seized control of the country’s major cities. To avoid the scourge of war, Hadid writes, some villages around the capital cooperated with the Russian army in an act of “betrayal.” Others, such as the village of Samashki, handed over their weapons and asked the Chechen fighters to leave in return for assurances of villagers’ safety from the Russian forces. Nevertheless, as Hadid relates, safety was far from assured, as the Russian troops committed atrocities such as the “Samashki massacre” in April 1995, during which more than 100 unarmed women, children, and elderly were killed after the withdrawal of the Chechen fighters.[4]

“The reoccurrence of that scene in al-Sham today” is astounding, writes Hadid, referring implicitly to the Russian-brokered agreements of “reconciliation” and “de-escalation zones” that were signed between the Syrian regime and the Islamist armed opposition throughout the conflict. (The “reconciliation” agreements have helped the Syrian regime to recapture opposition-held territories without fighting, in return for false assurances regarding the future status of the opposition fighters; the “de-escalation zones” have spared the regime having to fight multi-front battles.)[5]

Another parallel that Hadid draws between the experiences of Syria and Chechnya is the “the structural defect” in the strategy dealing with “the current of betrayal,” meaning those who betrayed the Islamic cause. In the case of Chechnya the chief traitor is understood to be Ahmad Kadyrov, a former military commander and religious scholar who would be co-opted by Russia and become president of Chechnya. Although the Chechen militants managed to assassinate Kadyrov in 2004, they lacked a “well-laid plan to deal with” his betrayal project, which had dire consequences for the future of Muslims. Hadid reserves greater vitriol, however, for the jihadi movement in al-Sham, whose negligence in dealing with the “intelligence-backed factions”—referring to HTS and other opposition groups that have cooperated with Turkey and other foreign states during the conflict—and poor planning and inexperienced practices have “cost the umma the elite of its leaders.” These are the AQ-affiliated Hurras al-Din seniors, who have been killed in drone strikes over the last two years by the U.S.-led international coalition.

Not all of Hadid’s ruminations on the past are critical, however. At one point he advises his readers to “think outside the box,” citing the example of the Chechen military commander Shamil Basayev, who in June 1995 attacked the southern Russian city of Budyonnovsk with just hundreds of fighters, leading to the capture of more than a thousand civilians and the killing of many others. The operation forced the Russians to initiate peace negotiations after an immediate ceasefire. Basayev’s strategy, which Hadid calls the “Caucasusization” of the struggle, aimed at transforming the Chechen conflict into a regional one that stretched across a huge swath of Russia and the former Soviet states in order to fatigue Moscow and embarrass it internationally. Citing Smith’s and Lee Myers’s books, Hadid provides other examples of Basayev’s military operations abroad, like the famous attack on the Moscow theater in October 2002, the Nazran raid in 2004 in the Republic of Ingushetia, and the Beslan School Siege in 2004, all of which resulted in a high Russian death toll despite the limited number of Chechen fighters involved.

Jihadi Sufism

In considering the failures in Chechnya and Syria, Hadid also turns a critical eye to the role played by Turkey in both cases. In contrast with the dominant jihadi Salafi narrative, which laments the demise of the Ottoman Empire and glorifies its past role as the guardian of Islam, Hadid lambasts the Ottoman sultans for neither defending their Muslim brethren nor supporting their resistance to the Russian Empire’s military expansion in the northern Caucasus during the 18th and the 19th centuries. How similar today is to yesterday, remarks Hadid, claiming that Turkey has abandoned “the Muslims to be slaughtered by the Nusayris” in al-Sham and conspired with the Russians in containing the jihadi movement there.[6]

In the past, according to Hadid, Islam in the northern Caucasus was “preserved” by what he calls “jihadi Sufism” (al-sufiyya al-jihadiyya), a term possibly coined by him and referring to those Sufis who adopted violence as a means of resistance to colonialism in the 18th and the 19th centuries. Hadid seems to anticipate the astonishment of his readers at seeing this term, noting that “we have become used to hearing only the term ‘jihadi Salafism’ (al-salafiyya al-jihadiyya).” In principle, jihadi Salafis consider the Sufi tradition to be heterodox on account of its embrace of bid‘a, or innovation, such as visiting the shrines of religious figures and revering saints. Sufis, according to jihadi Salafis, worship these shrines and figures and associate them with Allah, which renders these practices al-shirk al-akbar, or “greater polytheism.” Excommunicating Sufis and legitimizing jihad against them, however, have been contested by groups and figures within the sphere of jihadi Salafism.

Its “innovations” notwithstanding, Hadid praises jihadi Sufism for combating the British in the Sudan, the Italians in Libya, and the French in Algeria, in addition to safeguarding Islam in the northern Caucusus. His remarks echo those of other pro-AQ ideologues such as Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi and Abu Musab al-Suri, who, while acknowledging their shortcomings, have also praised jihadi Sufis and given them credit for protecting Islam throughout modern history.[7] IS, on the other hand, does not overlook the perceived flaws of Sufism, and so excommunicates its adherents. Tragically, its Wilayat Sinai militants carried out a gruesome attack on the Sufi mosque of al-Rawda in November 2017, claiming the lives of 305 people.[8] During the same month, IS published a video featuring one of its leaders claiming that IS had warned the Sufis in Sinai against practising their polytheism (shirk), “but to no avail.” Therefore, “their blood is to be shed.”

The Kadyrov of al-Sham

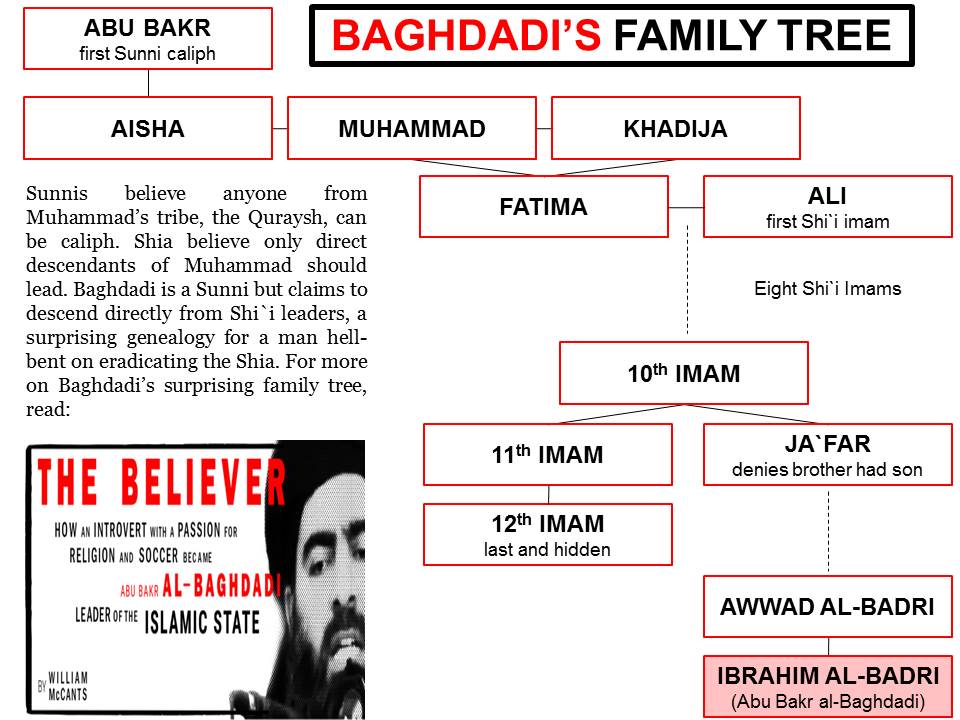

The assassination of former president Ahmad Kadyrov in 2004 did not harm the political forrtunes of his son Ramzan, who came to power in 2007, ushering in a new phase in Chechen history characterized by close ties between the younger Kadyrov and Russian president Vladimir Putin. In return for “submitting to Putin,” tightening control over the security situation in Chechnya, and executing national and international tasks assigned to him by the Kremlin, Ramzan Kadyrov was rewarded with fortune, power, and influence.

Hadid accuses Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, the leader of HTS, of playing the role of Kadyrov (both father and son) in Syria, except in al-Jolani’s case he is kowtowing to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as opposed to Putin. Describing al-Jolani as “Jolanov,” Hadid attacks him for dismantling the unity of the largest jihadi group (Jabhat al-Nusra) in al-Sham, facilitating or at least remaining silent regarding the targeting of jihadi leaders opposed to his policies, reducing the ideology of the jihadi group to one of narrow nationalism, embracing international agreements after much blood has been shed to oppose them, and establishing a department for issuing fatwas (dar ifta’) to provide religious cover for his policies. Hadid also condemns “Jolanov” for interfering with the spread of the jihadi movement outside his zone of influence by preventing Hurras al-Din senior Abu Julaybib al-Urduni, who was killed in December 2018, from moving to Daraa and establishing a jihadi group in southern Syria.[9]

According to Hadid, al-Jolani, much like the Kadyrovs with Putin, has been rewarded for his cooperation with the “rulers of Anatolia.” In return for his cooperation, Turkey has thrown open the border crossings to Idlib and left them unsupervised, allowing al-Jolani to take his “cut” of the foreign aid coming into the province and thereby enriching himself and his cronies. In the future, he says, al-Jolani hopes to be rewarded further by being appointed the unrivaled leader of this small part of Syria.

Strengthening or in Disarray?

Since the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, assessing AQ ’s strength has become a contentious debate among analysts and scholars of jihadi Salafism. While some believe that AQ is “much stronger” today than it was in 2001, others argue that the group is in “disarray.” In some sense AQ may be rightly seen as stronger today than it was on 9/11, given that it now has a network of affiliates from South Asia to North Africa. However, the group’s leadership structure appears to be in crisis, as Hadid’s essay attests. The final chapter in particular, which accuses both Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri of committing “strategic mistakes” in their approach to Iraq and Syria, suggests that the AQ leadership has lost the aura of its heyday.

As Hadid writes, following the death in 2010 of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, the former leader of the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI), bin Laden should not have accepted the appointment of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as the group’s emir for a one-year term pending further vetting as he did. Likewise, al-Zawahiri should have followed up on bin Laden’s decision, and he should not have accepted al-Jolani’s bay‘a, or pledge of allegiance, following the dispute between JN and ISI in 2013. Both leaders are criticized for failing “to fortify the solid core of the jihadi movement against rebellion and betrayal,” such fortification being “an essential building block for strategic success.”

Yet according to Hadid, bin Laden was a leader of far greater influence and ability than al-Zawahiri, and his death in 2011 was a key factor behind the “treachery” that would take place in Iraq and Syria. The loss of such a charismatic and powerful figure as bin Laden, one capable of remotely containing disagreements between the leadership and the group’s affiliates, “deprived the group of an important weapon in combatting any deviation that might afflict some commanders.” Without doing so explicitly, Hadid accuses al-Zawahiri of demonstrating feeble and ineffective leadership.

Indeed, the fact that al-Zawahiri’s directives were defied by both al-Baghdadi, when he refused to reverse the merger between JN and ISI and operate only in Iraq in 2013, and al-Jolani, when he announced the breaking of ties with AQ in 2016 against the wishes of al-Zawahiri, speaks volumes about AQ central’s level of influence over its subordinates. Under al-Zawahiri, as is seen in Hadid’s essay, AQ has lost much of the respect and influence it possessed during bin Laden’s life. As Marwan Shehade recently put it, “Who listens to al-Zawahiri today! He is not competent enough to lead an organization the size of AQ.”

One could conclude that Hadid is thinking much the same thing. Certainly, his essay supports the view that AQ, rather than strengthening, is indeed in a state of disarray. That this view is being articulated by a jihadi writer who supports AQ, and published on an AQ-affiliated platform, is all the more remarkable.

[1] For more about the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood in ’70s and ’80s, and the controversy over Marwan Hadid’s connections with the Fighting Vanguard, see Ahmad Mansour’s interview with Adnan Sa’ed al-Din, the fourth muraqib, or leader, of the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria: Shahid Ala al-‘Aser, September 9, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIusQVhw4cI.

[2] Dara Conduit argues that Marwan’s Hadid’s ideas regarding waging war against the Assad regime in 1970s led to the formation of the “The Fighting Vanguard.” See Dara Conduit, The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria (Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 34.

[3] Jan Hjärpe, “What Will Be Chosen From the Islamic basket?,” European Review, volume 5, issue 3, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-review/article/abs/what-will-be-chosen-from-the-islamic-basket/03AC9398D26B22B1ADC10FBD19097B2F.

[4] For more about the “Samashki massacre” see Michael Specter, “Russians’ Killing of 100 Civilians in a Chechen Town Stirs Outrage,” New York Times, May 1995. https://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/08/world/russians-killing-of-100-civilians-in-a-chechen-town-stirs-outrage.html.

[5] For a detailed account of the reconciliation process between the Syrian regime and the armed opposition, see Jusoor Study Center, The Reconciliation System in Syria: Societal Peace or War Strategy, October 2018. https://jusoor.co/details/نظام%20المصالحات%20في%20سورية%20سلام%20مجتمعي%20أم%20استراتيجية%20حرب؟/448/ar.

[6] “Nusayris” is a pejorative term commonly used by Salafis and jihadis to describe Alawites.

[7] See Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi’s introduction in Abu Anas al-Shami’s Sufism, p. 3 http://www.ilmway.com/site/maqdis/MS_4313.html. Abu Musab al-Suri, The Global Islamic Resistance Call, p. 1019.

[8] H.A. Hellyer, “The Dangerous Myths About Sufi Muslims,” November 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/11/airbrushing-sufi-muslims-out-of-modern-islam/546794/.

[9] This confirms Charles lister’s account in his article discussing the implication of HTS’s breaking of ties with AQ. Charles Lister, “How al-Qa`ida Lost Control of its Syrian Affiliate: The Inside Story,” CTC Sentinel, February 2018, https://ctc.usma.edu/al-qaida-lost-control-syrian-affiliate-inside-story/.