Guest Post: The Story of Eric Breininger

[Editor’s note: This post was written by Christopher Radler and Behnam Said, who are intelligence analysts based in Hamburg, Germany. For links to the original document, see the comments to the preview post.]

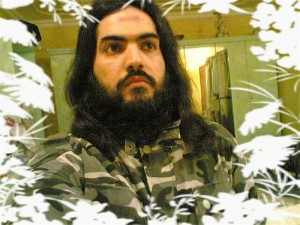

On 3 May a message announcing the death of Eric Breininger (b. 3 August 1987) and three of his fellow combatants was posted on several German jihadist websites. Breininger, who travelled to the border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan in the winter 2007, was one of the most infamous German jihadists. From Waziristan Breininger, a.k.a. “Abdul Ghaffar al-Almani”, sent several videotaped messages to the jihadist community in Germany, asking them to join the jihad or at least to support it financially. Since September 2008 the German Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) searched for Breininger, based on his assumed affiliation with a foreign terrorist organization.

A day after the announcement of his death, Breininger’s alleged autobiography, entitled Mein Weg nach Jannah (My Way to Paradise) was released on jihadi websites. The 108-page document mainly deals with Breiningers path into violent islamist militancy. It is not clear however, if Breininger wrote the document himself. In the messages he delivered from Waziristan, he spoke a very simple and often grammatically incorrect German. By contrast, the language of the published book is far more elaborate and correct. On the other hand, the content and details in the book argue for the authenticity of the document. Interestingly, the spelling of names differs throughout the book, which could indicate a collaborative effort. So we can assume that Breininger either 1) wrote it down by himself and had some help from his friends, or 2) told his story to some of his fellow jihadists and they wrote it down, as Spiegel journalist Yassin Musharbash suggested. Overall, however, we favour the first assumption.

After stating the reasons for writing down his autobiography, that is to say to disprove the lies spread by the media and to guide Muslims and non-Muslims to the path of Allah, he describes his conversion.

Radicalization and Recruitment in Germany

Breininger starts by telling us about his pre-Islamic life. Living together with his mother and sister since his parents’ divorce, he had the life of “a typical western teenager“, i.e. he went to parties and had relationships with girls. He calls this lifestyle “following condemned Satan’s way“ (p. 6). Breininger further describes his search for the meaning of life that initially did not lead to satisfying results. However, in his workplace he came into contact with a Muslim colleague who gave him the first lessons in the Salafi way of Islam and took him to a local mosque where he felt very comfortable.

One day, Breininger and his “mentor” (who remains unnamed) were on their way home from work. They ran into “Abdullah” (a.k.a. Daniel Schneider, member of the terrorist Sauerland cell who was recently sentenced to 12 years for plotting to bomb US targets in Germany) and a person named Houssain al-Malla. Breininger was introduced to Schneider and al-Malla. It was the latter who provided the final inspiration for Breiniger to convert. After his conversion he devoted himself to the study of Islamic audiolectures and books. He quit school and spent more time with his new “brothers”. In the meantime, his former girlfriend had become Muslim and subsequently they contracted their marriage according to Islamic Law. It turned out, however, that this girl converted only to please Breininger, not out of genuine conviction. So Breininger ended the relationship and moved into Daniel Schneider’s appartment, where both of them regularly received al-Malla. Together they consumed a lot of jihadist propaganda downloaded from the Internet. The effect was dramatical:

“I knew that I had to take measures against the crusaders who where humiliating our brothers and sisters. Also every Muslim should stand up for a life according to the law of Allah and for the reason that we must build an Islamic state” (p. 53).

Breininger also states that they were appalled by the news from torture and prison abuse. Here we have another proof that it is these grievances caused by westerners themselves that help to radicalize.

Religio-ideological development

Breiningers first mentor in Germany invited him to his home and told him about the unity of God (tawhid) and the fundamentals of belief (´aqida). Breininger lays down the fundamentals of his belief by copying and pasting part of a book into his autobiography, dealing with the doctrine of tawhid.

Later on, after meeting Daniel Schneider and Houssain al-Malla, Breininger learned about the doctrine of “loyalty (towards believers and god) and enmity (towards infidels especially)” (al-wala` wa-l-bara`). Loyalty and enmity, Breininger tells us, are “the most important fundamentals in islam and are the two main conditions for the true belief” (p. 56). He underlines his point by quoting the former leader of the Iraqi al-Qaeda (AQ) branch Abu Mus’ab az-Zarqawi (p.58).

In the following part he writes about Jihad as an individual duty (fard al-´ayn), noting that “every Muslim who does not attend his duty to go out to follow Allahs path and to fight” is obviously a sinner (fasiq) and will be punished by God (p.59/60). As support he quotes the pamphlet The Defense of Muslim Land – The First Obligation after Iman by Abdullah Azzam.

Travelling for Jihad

After Breininger’s decision to participate in violent jihad and his abortion of his original plan to go to Algeria, he travels to Egypt and studies Arabic in Cairo. Four months later al-Malla joins him there and eventually convinces Breininger to travel to Afghanistan. Thus they went by airplane to Iran and subsequently took a bus to Zahidan near the Pakistani border. With the help of a human trafficker named “Mustafa” and after bribing an officer at the border they proceeded their journey to Waziristan covered with burqas (!) in a cab. Finally arrived at a safehouse of the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU), they were joined by mujahidin from Tajikistan and Turkey and were transferred to Afghanistan. Here they started a training which outlines as follows:

– Fajr prayer, dhikr, sports and stretching, one minute for breakfast, weaponry, time until dhuhr-prayer for memorizing

– Dhuhr prayer, tactics and “Anti-terror-fighting“ (close combat fighting)

– Asr Prayer, one minute for eating (bread and tea), weaponry-test (in case you failed you received punishment), dhikr

– Maghrib prayer, memorizing Qur’an until Isha-prayer

– Isha prayer, one hour guard duty once in a while

After al-Malla leaves the group for reasons unknown to Breininger (!) the latter’s situation begins to deteriorate because there were no other German-speakers amongst his comrades. Nevertheless, he completes his first training which is immediately followed by a second one. Here, the focus lies on the training with heavy weapons like recoilless guns, anti-aircraft weaponry and mines. Also the usage of GPS and radio equipment was part of the training. After moving to the so called “Istishhadi-house” (house of martyrdom-seekers) he describes some operations, one of them conducted together with mujahidin from the Taliban and AQ. It raised our eyebrows when we read that a chemical agent was used in a martyrdom operation against “murtaddin” in Khost. According to Breininger more than 100 “apostates and infidels” died (allegedly partly in the aftermath of the assault when the chemical agent began to take effect).

Assuming that Breiningers account is true, this suggests ongoing cooperation between different organizations in Afghanistan. It also suggests, very worryingly, that Taliban and/or affiliated groups may be using crude chemical weapons.

German Taliban Mujahidin

After three years as a member of the IJU Breininger still had problems communicating with his comrades. When he was approached by his commander and told that some German Muslims had recently completed their training and planned to join the Taliban, Breininger decided to do so as well. The Taliban had no objections to the founding of a subgroup, so the “German Taliban Mujahidin” (GTM) emerged. Thanks to Breininger´s account we finally know about the background of this group that virtually emerged out of nothing and kept analysts busy for a long time. Especially since the Taliban never officially approved the GTM as part of their movement.

Threatening the Far Enemy

Breininger ends his story with an appeal to German Muslims to support the jihad financially:

“If the brothers would buy one doner kebab less a week it would be possible to buy almost 20 sniper bullets to fight the kuffar” (p. 102).

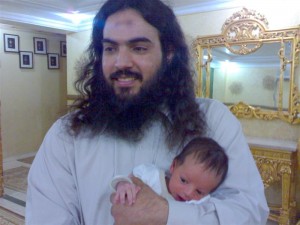

This appeal is followed by a call to Muslims to join the mujahidin because many of them want to start a family. The environment allows the breeding of children “free from the kufr of western society (…) This new generation of mujahidin grows up multilingual. They usually learn Arabic, Turkish, English, Pashtu, Urdu and their parent’s tongue” (p. 103).

Breininger’s conclusion gives us an idea about the long-term strategy of jihadist groups and clearly shows that the threat for Western countries is anything but averted yet:

“With God’s permission this offspring will become a special generation of terrorists [sic] that is not listed in any of the enemy’s databases. They speak their enemy’s languages, know their manners and customs and are able to mask and infiltrate the land of the kuffar because of their appearance. There they will insha’allah be able to conduct one after another operation against Allah’s enemies thereby sowing fear and terror in their hearts” (p. 104).