Battlefield Yemen: The Islamic State’s Challenge to AQAP

Since the caliphate declaration of late June 2014, Yemen has emerged a key battleground in the intra-jihadi struggle pitting the Islamic State against al-Qaeda. The country hosts what is arguably al-Qaeda’s most prestigious affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). But as far as the Islamic State is concerned, that organization ceased to exist when the caliphate was declared. Thereafter all jihadi groups were expected to dissolve themselves and incorporate within the all-supreme caliphate.

Preemptive bay‘a

In mid-November, the Islamic State, driving home this point, officially declared its “expansion” to Yemen, among other target countries, proclaiming “the dissolution of the names of the groups in them and declaring them to be new provinces of the Islamic State.” A series of bay‘as— statements of allegiance to Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi—were issued simultaneously on November 10 from Yemen, Arabia, Egypt, Libya, and Algeria. Three days later, Baghdadi “accepted” the pledges, conferring on the new territories the status of “provinces.” In two of the countries—Egypt and Algeria—the bay‘as came from preexisting jihadi groups known for their ties to the Islamic State. But in Yemen the statement of allegiance came not from that country’s well-established jihadi group—AQAP—but rather as a challenge to it.

Al-Qaeda’s Yemeni affiliate, as Saud al-Sarhan has detailed in an important new study, is deeply divided over which side in the jihadi civil war to support: the Islamic State or al-Qaeda. Previously, the group had tried to adopt a more-or-less neutral stance. But the bay‘a, apparently calculated to force AQAP’s hand, compelled it to choose sides. And it definitively chose al-Qaeda. Predictably, pro-Islamic State jihadis online are outraged. The pro-Islamic State Yemeni community, however, has been more nuanced in response.

Yemen’s Islamic State supporters

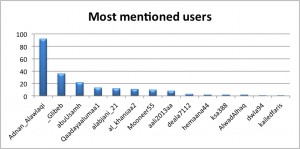

As Sarhan noted, the two most noteworthy Yemeni promoters of the Islamic State are ‘Abd al-Majid al-Hittari (@alheetari), an independent preacher, and Ma’mun Hatim (@sdsg1210), an AQAP scholar. Both were early supporters of the Islamic State when its conflict with al-Qaeda heated up in late 2013, and both lent their imprimaturs to the Ghuraba’ Media Foundation’s February “Statement of Brotherhood in Faith for Support of the Islamic State.” Signed by 20 jihadi scholars, this called on all Muslims fighting in Syria to give bay‘a to Baghdadi, and on all Muslims across the world to support the Islamic State.

Both Hittari and Hatim were likewise supportive of the Islamic State’s declaration of the caliphate on June 29, 2014. Hittari wrote an essay in its favor, telling Baghdadi he would “urge the Muslims [of Yemen] to prepare to obey you.” Hittari furthermore endorsed Baghdadi’s decision upon declaring the caliphate to dissolve all competing jihadi groups across the world. As the caliphate declaration had noted, “the legitimacy of your groups and organizations is void.” Concurring, Hittari told Baghdadi: “I believe that your dissolution of the Islamic groups is a successful step on the path to uniting the Muslim community around its state and its emir.”

Hatim, for his part, congratulated those who “made the dream [of the caliphate] a reality.” And in mid-June he also gave his support to the strategy of dissolving other groups. In a long audio recording online he addressed “my brothers in the branches of al-Qaeda, in all countries and regions and lands,” urging them to unite within the Islamic State, which would be “the first of your steps toward [achieving] victory and political capability.” Ma’mun Hatim did not speak for the entire AQAP leadership, however.

Bay‘a for bay‘a

Unlike al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghrib, AQAP did not issue an early statement rejecting the Islamic State’s caliphate. Nor did it adopt the central al-Qaeda leadership’s dismissal of the Islamic State as a mere “group” as opposed to a “state.” AQAP sought to walk a neutral line. But the surprise bay‘a on November 10 changed that.

A week and a half later, in a video dated November 19, AQAP came out with its first significant refutation of the Islamic State, contesting its claim to have dissolved AQAP and to have founded a province in its stead. In a 30-minute address, senior AQAP scholar Harith al-Nizari reiterated his group’s desire for neutrality in the intra-jihadi conflict in Syria, urging all parties to consult an independent shari‘a court. But he denounced what he called the Islamic State’s effort to “export the fighting and discord [in Syria] to other fronts,” namely Yemen.

Two steps taken by the Islamic State were in particular disagreeable. The first was the caliphate declaration, which Nizari deemed illegitimate. Neither the proposed “caliphate” nor its “caliph,” he said, met the necessary conditions stipulated in the shari‘a. Furthermore, the time was not right for appointing an “imam,” or caliph. The second was the Islamic State’s more recent effort to eliminate AQAP via the preemptive bay‘a. “We call on our brothers in the Islamic State,” Nizari said, “to retract the fatwa to dissolve the groups and divide them…We consider them responsible for what could result…of the shedding of unlawful blood on the pretext of expansion and extending the authority of the state.”

Clarifying AQAP’s ultimate loyalties, Nizari defended Ayman al-Zawahiri’s al-Qaeda against charges of “deviation,” and he rejected the idea that AQAP could simply fold and gave bay‘a to the Islamic State as that would violate the terms of the group’s current bay‘a to al-Qaeda. He then reaffirmed his group’s loyalty to the al-Qaeda leadership: “We reject the call to split the ranks of the mujahid groups, and we renew the bay‘a to our commander, Shaykh Ayman al-Zawahiri, and, via him, the bay‘a to Mullah ‘Umar.” The nature of this latter bay‘a to Mullah ‘Umar was left unspecified, but it plays to al-Qaeda leaders’ recent efforts (see here and here) to cast the Taliban ruler in a caliphal role.

Refuting AQAP

Harith al-Nizari’s address was of course met with condemnation from pro-Islamic State writers online. Four scholarly refutations were quick to appear (see here, here, here, and here), all by pseudonymous authors. Three of them are prolific and well-known—Abu Khabbab al-‘Iraqi (@kbbaab), Abu Maysara al-Shami, and Abu l’-Mu‘tasim Khabbab (@abu_almuttasim). The latter’s refutation earned the endorsement of Hittari.

These pieces made several of the same points. First: AQAP’s pretense of neutrality is a sham, for there can be no neutrality. One is either on the side of “Divine Truth” (the Islamic State) or on that of “falsehood” (al-Qaeda). Second: Against Nizari’s claim to the contrary, the caliph and caliphate of the Islamic State no doubt meet the “conditions” mandated by Islamic law. On this matter AQAP is simply “lying” and deceiving; its leaders’ lust for power is preventing them from admitting what they surely know. Third: The Islamic State is no source of “discord”; rather it is the intransigence of groups like AQAP, which refuse to join the caliphate, that accounts for disunity. Fourth: AQAP’s claim to have a bay‘a to Mullah ‘Umar is incoherent. As one author points out: “Why is it OK for Mullah ‘Umar to gather bay‘as from territories in which he has no authority…while that is forbidden for Baghdadi?” And did not Nizari say that this is not the right time for appointing a caliph? If so, then how can he give Mullah ‘Umar bay‘a as putative caliph?

The anger and frustration in these refutations are apparent. Yet not all pro-Islamic State jihadis castigated Nizari so ardently. A prominent one of their number—a certain Abu ’l-Hasan al-Azdi—actually cautioned against attacking AQAP, urging measured argument. Responding to Abu Maysara al-Shami’s refutation, he said it would be wise not to antagonize jihadis who have yet to support the Islamic State; such argumentation only deepens the “chasm of the conflict.”

Dueling approaches in Yemen

In Yemen itself, the events of November drew different responses from the two main pro-Islamic State advocates there, ‘Abd al-Majid al-Hittari and Ma’mun Hatim. Each now represents a different way of being a pro-Islamic State jihadi in the country.

Hittari was unreservedly supportive of the Islamic State, applauding its “expansion” and condemning AQAP’s response. AQAP leader Nizari, he said, had failed to “comprehend the wisdom of the [current] stage [of jihad].” That is, the stage of the caliphate. One is either with it or against it. He encouraged the Islamic State to hold fast to its current strategy in Yemen.

Hatim was of a different mind. In a series of revealing Tweets, he argued that the Yemeni bay‘a to the Islamic State of November 10 was flawed. He did not denounce those who gave the bay‘a. Indeed, he revealed that he knows who they are: “the majority of them are among the best people I have known, and a large number of them are my students and brethren.” Nor did he reject the notion of the Islamic State’s expanding: “We are not opposed to the expansion of the [Islamic] State.” The problem was the means, not the ends: “We have to consider the correct and legitimate means for [achieving] its expansion.” In the present circumstances of Yemen, “the harmful consequences that will obtain from the bay‘a and the proclamation of a new group in one theater are many, many times greater than the desired benefit of that announcement and the division.” With regard to those circumstances, he spoke of “facing a fierce, multi-front war” in Yemen, referring to AQAP’s battles with the Yemeni government, the Houthi Shi‘a movement, and the United States.

From Hatim’s perspective, there are two ways to support the Islamic State in Yemen. “We,” he said, referring to pro-Islamic State jihadis, “are before two choices. Either we rush the bay‘a, meaning division, separation, weakness, and failure, or we act patiently in the coming days, ensuring that opponents’ understanding is rectified and their views clarified.” What Hatim wants—“what we strove for and called for”—is “a group bay‘a,” meaning a bay‘a given by AQAP to the Islamic State, not one meant to undermine the group. But that has yet to materialize. Aspiring to such an outcome, however, remains in his view a better option than fragmenting Yemen’s jihadis.

Some jihadis online have faulted Hatim’s siding with AQAP. As one representative critic stated, “maybe war”—not patience—“is the inevitable treatment for the ailment.” But at least one major pro-Islamic State jihadi online, Abu Khabbab al-‘Iraqi, defended the Yemeni to a degree. Hatim should be reproved for “his hesitation to give bay‘a to the Islamic State and come under its banner,” he said, but this should be done as to a “loved one,” not an enemy.

The Yemeni third way

There would thus appear to be a bit more flexibility on the part of pro-Islamic State jihadi ideologues when it comes to Yemen as opposed to elsewhere. At least two of these—Abu ’l-Hasan al-Azdi and Abu Khabbab al-‘Iraqi—have told their peers to tone it down in criticizing those Yemenis reluctant to join the caliphate. This is a flexibility hitherto absent from pro-Islamic State jihadi discourse, which has previously shown no tolerance for any kind of neutrality. It is as yet unclear whether the Islamic State’s new Yemeni “province” will really compete with AQAP. But it seems likely that any confrontation will be significantly delayed by Hatim’s staking out of a plausible Yemeni third way.