At Jihadica, we usually don’t weigh in on policy debates. I’m reluctant to break that tradition but I have a few thoughts on countering violent extremism that I’d like to workshop with Jihadica readers before turning them into something more.

The United States and its allies devote considerable financial and human resources to countering violent extremism (CVE). Nevertheless the definition of CVE is unclear, ranging from fighting bad guys to creating good guys. This lack of precision makes it hard to design, execute, and evaluate CVE programs and makes it easy to slap the CVE label on all manner of initiatives, including many that seem to have little to do with stopping terrorism and might otherwise be cut by Congress. The lack of precision also inhibits thinking about whether the CVE enterprise is worthwhile and what should constitute it.

In the interest of clarifying the activities covered by CVE and encouraging debate on their relative merits, I propose the following definition: Reducing the number of terrorist group supporters through non-coercive means. (I might also propose a new label and acronym for this activity but “CVE” is so bland and prevalent that it’s not worth jettisoning.)

This definition has several things to recommend it:

- It is broad enough to cover most of what people describe as CVE (or, in UK parlance, “Prevent”).

- It is narrow enough to exclude insurgent organizations and gangs that don’t primarily attack civilians for larger political objectives (an activity usually called “terrorism”).

- It suggests a metric: reducing the number of a terrorist group’s supporters. The focus is not on reducing support for ideas, which is difficult to judge, but rather support for specific organizations that embody those ideas and seek their realization, which is easier to document and more closely related to criminal behavior.

- It excludes coercive kinds of “countering” activity that are better left to law enforcement and militaries (e.g. arresting, killing).

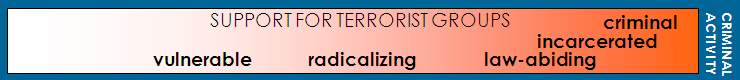

- It acknowledges that there is a spectrum of support, ranging from lone wolves to bona fide members of a terrorist group. Moreover, support does not necessarily imply criminal behavior. The “supporter” label applies to anyone who expresses uncritical enthusiasm for a terrorist group’s program and actions.

To operationalize this definition of CVE, two questions must be answered. First, what terrorist groups deserve programmatic attention? Typically, they are those deemed to pose the greatest threat to a country. Second, what kinds of supporters deserve programmatic attention? Is it people vulnerable to becoming supporters? People who are becoming supporters? Law-abiding supporters? Criminal supporters? Incarcerated supporters? Answers to these second set of questions vary from country to country, resulting from differing assumptions about who is amenable to positive change and how they are identified; unique laws, national security priorities, and political culture; and competing interests and missions of the country’s institutions. For the U.S. government, CVE programming focuses on people who are vulnerable to becoming supporters of al-Qaeda. (In a follow-up post I will explain why a narrower focus on law-abiding supporters might be more useful.)

There is at least one objection to the definition above: Its resulting programs would not cover terrorists like Anders Breivik or the Unabomber, who did not profess loyalty to, or common cause with, any terrorist group. But ideologically-independent and socially-reclusive lone wolves like these are extremely rare and extremely difficult to detect. If a CVE definition were crafted to cover them, it would be so broad as to be useless, which is the current state of play.